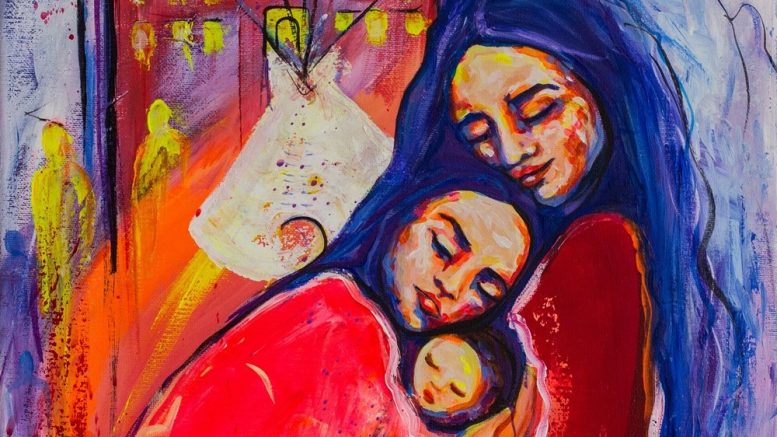

(ANNews) – The stunning painting that appears on the cover of the January 2019 edition of Alberta Native News is entitled ‘Three Generations – series three’ by the very talented and eclectic multi-disciplinary artist Lana Whiskeyjack.

The theme of generational love and caring is especially important to Whiskeyjack against the backdrop of the generational trauma suffered by Indigenous survivors of the Indian Residential Schools, their families and their communities. She captures this in her painting through her brilliant use of colour, broad brushstrokes, paint splatters, ghostly background images and serene facial expressions.

Whiskeyjack discussed these concepts and more at the first annual Film Festival of Time held from January 4 – 6 at Metro Cinema at the Garneau Theatre. The vision of the Festival was to explore the relationship between art and community, bringing light to Indigenous, Canadian and International films with historic context.

Whiskeyjack discussed these concepts and more at the first annual Film Festival of Time held from January 4 – 6 at Metro Cinema at the Garneau Theatre. The vision of the Festival was to explore the relationship between art and community, bringing light to Indigenous, Canadian and International films with historic context.

The festival, hosted by Zsofi, began with a gala on the evening of January 4. The gala featured the top submitted films and included Indigenous inspired appetizers, a silent auction that showcased art by local Indigenous artists, provided by Wakina Gallery and Lana Whiskeyjack as keynote speaker.

Lana is a gifted multi-disciplinary artist, educator and motivational speaker and a proud Cree woman from Saddle Lake First Nation. She gave a heartfelt and inspiring keynote address about the meaningful relationship between art and community.

She said, “Louis Riel is quoted as saying that our people will sleep for one hundred years and when they wake up it will be the artists who give them their spirit back. I think that speaks a lot about what we’ve been through, what we’ve survived and how resilient we are.”

It also speaks to the important role that artists have in Indigenous communities.

“We are now experiencing an Indigenous renaissance,” continued Lana, “where our youth are hungry for knowledge about culture and where they come from. We are also at a time when a lot of our elders are passing on and taking that knowledge with them. But right now, there is also a beautiful thing happening where we are returning to our culture and we’re returning to our ceremonies and our languages and medicine.”

“The medicine we’re born with is always there,” said Lana, and telling stories through art and film is an important way to revive the medicine and connect the generations.

Whiskeyjack discussed the impact of the Indian Residential Schools on Indigenous communities. She said that discussing the generational trauma from residential schools is a very difficult conversation to have “and as a Cree woman it is a very difficult conversation for me and my family. A lot of my art for the past 10 or so years has been about exploring that history and the generational effects of the Residential Schools and learning to find the words to be able to speak about the trauma and learning also about the beautiful parts that came from overcoming some of that trauma. But after having gone to that place for exploring the trauma, you don’t want to stay there but that is a difficult concept for non-Indigenous people to understand.”

She said that it is important to have the difficult conversations about racism and residential schools, but the end result should not be pity. Whiskeyjack used an anecdote about her aunty and the Blue Quills Residential School Tours to illustrate the point. She said that knowing the history of the school is important but “my aunty would say don’t feel sorry for me but do feel and use that feeling to help change your behaviour.”

Multi-disciplinary artist Lana Whiskeyjack delivered the keynote address at the Film Festival of Time held in Edmonton earlier this month.

Whiskeyjack said, “It’s the same thing with art and film and sharing our stories. We want to make sure these stories are told – and that we are travelling not just from the head but from the heart. That was what my Elder would always say – the longest journey is from the head to the heart.”

“One of my mentors – Alex Janvier from Cold Lake Alberta – told me that if you want to paint something ugly make it beautiful. Those words resonate for us as artists because when we are creating art, we are sharing a deep part of our soul. It is a beautiful courageous place to be. For the viewer of the art, it is a courageous act to listen and to reflect and if possible, to even have a conversation afterwards. When we are looking at the work being done by so many indigenous artists, it is bringing that value of our relationship back.”

“It makes me think about the prophecies and the big changes that are taking place in our world,” explained Lana.

Lana Whiskeyjack and Film Festival of Time organizer Jonathon Zsofi.

“We are at a time now where our scientific knowledge is catching up to our Indigenous knowledge and that is part of the prophecies. We are returning to our Indigenous peoples to learn that way of coming back to balance with our land, our languages, our communities and our different nations.”

Whiskeyjack discussed the vitality of Indigenous languages.

“It is important for me as a Cree woman to learn the language,” she said. “Even though I grew up around Cree speakers, I am not fluent in the language, and my pronunciation is not great. I get teased about it but still it is very important to use what I can, because it connects me to the land, and helps me honour the people who came before me and to the people who will come after me.”

In Indigenous circles people speak about the importance of making decisions based on the impact they will have on the next seven generations. This concept is important to Lana.

She explained, “When I was doing my research about intergenerational traumas resulting from residential school it made me think of my aunties who told me that you know you have led a long life when you are able to meet your great grandchildren and pass that knowledge on them. It made me think of my great grandfather who lived at a time when his ceremonies were outlawed and he had to take his culture and dances underground or face going to jail.

“I remember his birthday; he lived to be 107. He didn’t speak much English, but he serenaded us with his music. This was a man who could make horses dance with his song. He was my grandmother’s father and to think of what he endured to meet me. There were three generations that connected me to him and those memories. And now I have a daughter and she has a daughter and in one more generation I’ll get to meet my great grandchild. So if you think of the three generations that passed and the three generations that I’ve come to know, that will be seven generations.

“The work that we do now as artists and the stories that we tell will connect the generations and slowly break the cycles of trauma. The more you know about where you come from and the more information you have, the better able you are to make positive decisions for that generation and for the generations to come.”

“This is a time of reconciliation,” concluded Lana. “That is a bit of a trigger word in my community. Some pronounce it “wreck” n ciliation and think of it as just another way of assimilation. But it takes a different meaning if you look at it in your own life as having reconciled with the past and looking at what you’re going to do for the future. It opens the dialogue from reflecting on this world as it is, to realizing the world as it could be.”

The artist then thanked the Film Festival organizers for inviting her to participate and wished them and those in the audience all the best for a wonderful festival.

Festival of time organizer Jonathon Zsofi thanked Lana for her inspirational keynote address and introduced the screening of several Indigenous shorts including the globally award winning “In the Beginning was Water and Sky” and “Gas Can.”

Be the first to comment on "Feature artist for January 2019: Lana Whiskeyjack"