by Brandi Morin

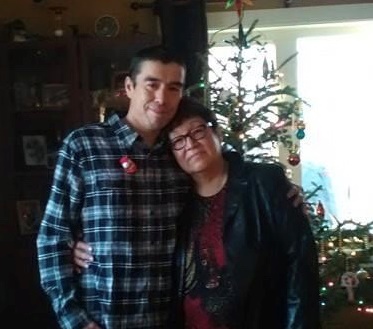

Dene grandmother Alice Rigney with one of her three grandchildren. “My grandson said: I don’t want to die…I hug him, and say stay home and I’ll protect him.”

(ANNews) – Alice Rigney, 68, peeks out her kitchen window to see how the weather is looking outside. But, as she pauses during a telephone conversation with Alberta Native News on Tuesday April 21, she relays a disappointing cold, and snow blowing scene.

“I’m getting cabin fever in here,” she explains of being homebound for over three weeks in her small community of Fort Chipewyan in Northern Alberta. “I’ve done a lot of reading; cleaned out I don’t know how many drawers,” she laughs, and then her voice momentarily is silent again.

“I don’t listen to much news or go on Facebook too much. Sometimes I get anxiety, or depression. My husband is gone, and this is a time I would really need him.”

Alice, a widow, is in lockdown along with her three grandchildren that she cares for. They’re keeping safe from the threat of the Coronavirus.

Fort Chipewyan is the oldest community in Alberta and is made up of mostly Metis and First Nations residents. It sits on the northwest peak of the immense Lake Athabasca, approximately 230 KM north of Fort McMurray. Many community members there still practice traditional lifestyles like hunting and trapping.

In March local officials formed a partnership to officially close off the town from the outside. Like many Indigenous communities across Canada, Fort Chipewyan is more vulnerable to an outbreak of COVID-19, due in part to its remote location and limited medical resources.

“We have to protect our people,” said Mikisew Chief Archie Waquan on implementing a strict 11 p.m. to 5 a.m. mandatory curfew and blocking access to the only roads in or out. Even the airport is closed, except for essential service deliveries. The community must take drastic precautions to prevent the Coronavirus from arriving, he said.

Fort Chipewyan Alberta.

“In my opinion, it’s dumb,” says David Stewart, 36, who runs one of the two gas stations in Fort Chipewyan. He’s also a member of the Mikisew Cree and not too worried about the virus coming there. He says young people not respecting social distancing and “partying” openly have ruined it for everyone.

“The curfew is too much. We’re not kids. There’s a handful of kids drinking and walking around the community yelling at night,” said David, “But the parents of those kids are responsible for them – those kids should’ve been sat on at home.”

But Chief Waquan stressed leadership isn’t taking chances.

“We are serious about what we are doing. A lot of the young people don’t understand what COVID is even about. We aren’t trying to keep them under wraps, we are trying to keep them safe,” said Waquan.

Fort Chipewyan officials employ a security team to patrol the community to ensure everyone is abiding by the rules at night. Anyone caught outside the designated hours receives one warning. “Further non-compliance to the policy will result in the cancellation of any future financial disbursements and/or considerations,” read a community bulletin posted on Mikisew Cree First Nation Facebook page.

Fort Chipewyan burial ground from the 1921 Spanish Flu epidemic.

As a boy Waquan remembered his father speaking of the Spanish Flu epidemic that hit the community hard, and he doesn’t want a repeat.

“He told us they couldn’t bury them (dead) fast enough,” said Waquan.

Alice, who is a respected elder in Fort Chipewyan, also remembers the sad stories her mother told her of the pandemic.

In 1921 the Spanish Flu killed countless people there and mass graves were dug. The bones of those lost to that influenza pandemic, which was cited as the worst influenza mortality event of all time, still lay under the town’s Northern Store.

But another burden is just over the horizon. A burden of grief – Alice is counting the days to the three-year anniversary that her son Keith Marten, 45, disappeared on a hunting trip.

“It’s painful to remember…I loved him his whole life and I will miss him for the rest of my life!”

Alice and her son Keith Marten, who died tragically on a fishing trip three years ago.

Keith was one of four hunters from Fort Chipewyan who vanished from the Rocher River north of town.

The bodies of all four were recovered over a two-month period. It was a devastating tragedy for the tight knit community of about 1,000 and drew in outpourings of condolences from across Canada.

Alice had her son’s remains cremated and sprinkled them at the top of a hill overlooking Lake Athabasca. It’s comforting for her to know his memory lives on.

The anniversary will be difficult. She’s preparing her heart for Thursday. Prayer and journaling help her get through the stress. And it’s the will to be there for her living children and grandchildren that keeps her going these days, she says.

She is upfront with her younger grandchildren about what’s going on in the world. She explains to them reasons why they can’t leave the house right now.

“My six-year-old grandson says, ‘I don’t want to die’…I hug him and say stay home and I’ll protect him,” she said.

“I always have hope and as long as the community thinks the same way, that hope will become reality. I look forward to the day it (COVID-19) will end. We will be dancing in the streets!”

Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation Chief Allan Adam said taking preventative measures will help save lives. He’s been closely following news of the outbreak as it makes its way around the globe. And he doesn’t want ACFN to succumb to deaths like the Navajo Nation, south of the medicine line. Compared to the State of Arizona, cases of infection and deaths from COVID-19 are 10 times higher in the Navajo Nation. Its vulnerability to the pandemic is an example, he says.

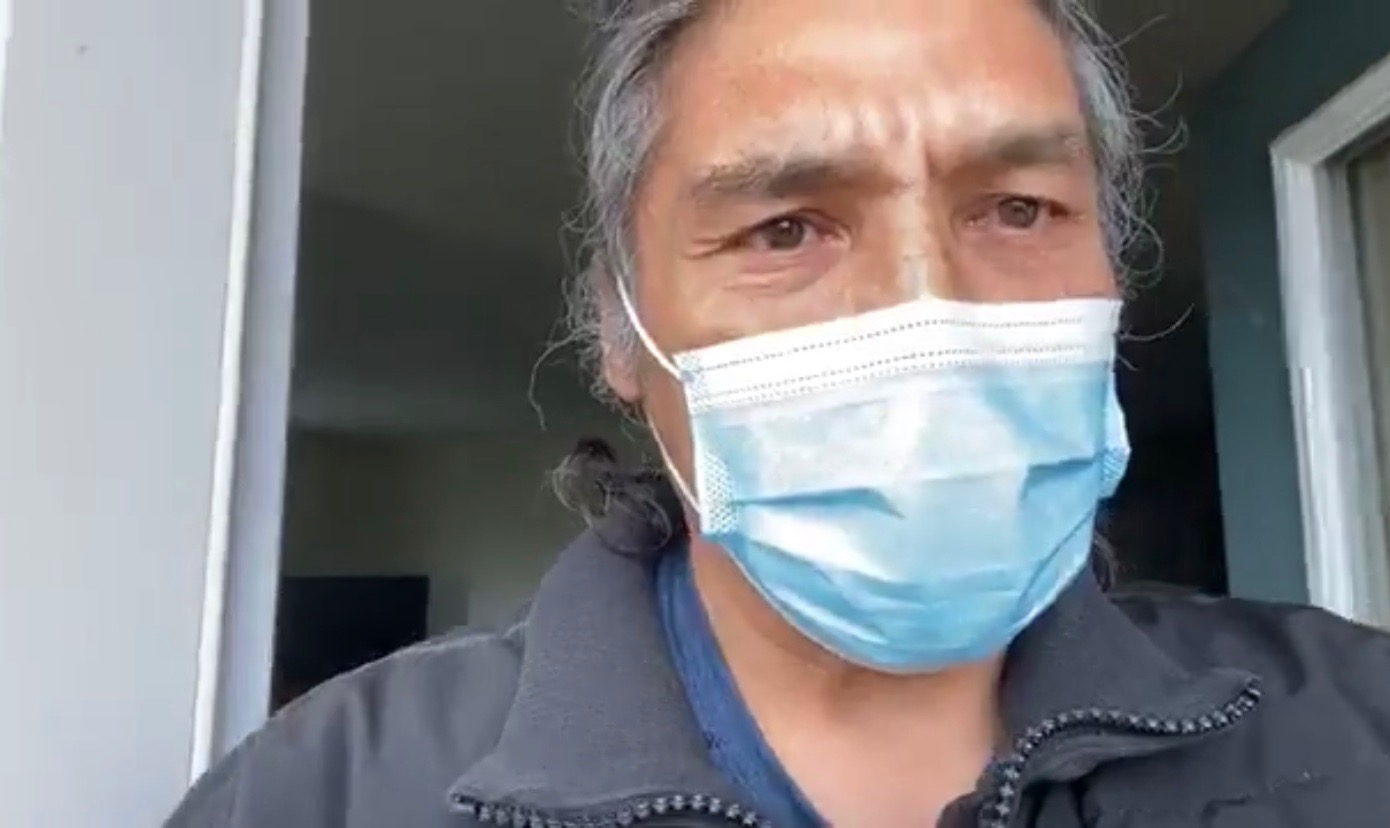

Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation Chief Allan Adam: “Taking preventative measures will save lives.”

This week the Athabasca Tribal Council partnered to offer a 24-unit isolation space at a hotel in downtown Fort McMurray. Medical personnel are on stand-by to care for incoming members.

“We’ve been working hard to ensure our members are secure,” said Adam via a Facebook video post shared Monday. “So, if someone develops COVID-19 symptoms, some of our members may be shipped out of Fort Chip or other nearby communities and sent to Fort McMurray to be sent to the staging area. We’re making sure if things come to this, and hope to God that it doesn’t, but at least we have units set aside for isolation. Stay home. Stay safe and take care.”

Currently there are no reported cases of COVID-19 in Fort Chipewyan. There are four active cases in Fort McMurray. So far, 141 Albertans have been hospitalized due to COVID-19 with 39 of those treated in intensive care units.

Fort Chipewyan also has isolation units available for anyone presenting with COVID-19 symptoms. But Chief Waquan is praying they stay empty.

“We are hoping we never have to use them,” he said.

What do I have to do when I get to fort McMurray do I have to stay in hotel in fort McMurray tomorrow when I get to fort McMurray .