By Jeremy Appel, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

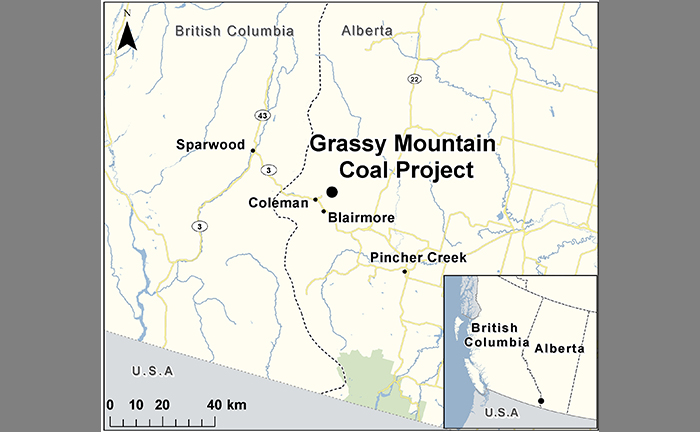

(ANNews) – The Alberta government announced on Feb. 8 that it’s backtracking on its removal of the province’s coal policy to permit open-pit mining on the Rockies eastern slopes. However, this decision has no bearing on the controversial Grassy Mountain project in Blairmore.

That’s because the coal policy divided the eastern slopes into four categories, banning all mining in Category 1 and open-pit mining in Category 2, with lesser restrictions in Categories 3 and 4. Grassy Mountain is Category 4, so open-pit mining was already permitted there.

While opposition continues to mount against the Grassy Mountain project, including among First Nations, the leadership of Treaty 7 nations continue to support the project, including those who had vigorously opposed the removal of the coal policy.

“It is not a hole in the side of a mountain, where people are going in with pickets and chipping at rocks. Open-pit coal mining is an extremely invasive method of extracting coal,” Kainai Nation member Latasha Calf Robe, who founded the Niitsitapi Water Protectors to oppose the Grassy Mountain Project, told the Forgotten Corner Podcast. “They literally blow up the mountain.”

The Blood Tribe and Siksika Nation filed a court challenge to the removal of the coal policy. It’s unclear whether it will proceed now that the government has committed to reinstating the policy in some capacity. The government said they’re allowing exploration that’s already under way on Category 2 lands to continue unabated.

“Kainai has a connection to the Crowsnest Pass region that dates back more than ten thousand years,” reads a statement from the Blood Tribe.

“The headwaters of the Oldman River Basin are sacred to the Blackfoot Nations and their way of life. Alberta acknowledges this reality in its land use plans for the region and committed to consulting Kainai and other First Nations on key decisions. Even so, the Government of Alberta made its hasty decision to strip protection of the area without any consultation.”

Regardless, both bands’ leadership continue to support Grassy Mountain.

The leadership of the Piikani Nation has gone all-in on support for coal, endorsing the UCP government’s removal of the coal policy.

In a Jan. 20 statement, Piikani Nation Chief Stanley C. Grier reiterated his unmitigated support Grassy Mountain, saying band councils are the only people authorized to speak on behalf of their membership.

“Without hesitation, the Piikani Nation, fully endorse the Grassy Mountain initiative as this site has been previously developed, disturbed, and laid dormant for at least 45 years,” wrote Grier.

“Back then Piikani Nation was never consulted at all and (there is) no indication that any type of environmental standards were applied at that time.”

Grier touted the employment and revenues he says the nation will receive from it.

“Responsible resource development can create thousands of good-paying jobs, something that our neighbours in surrounding areas have taken advantage of for decades,” he said, emphasizing that there continues to be global demand for steel, which is made with the same metallurgical coal that Grassy Mountain is slated to produce.

The nation underwent consultation that involves traditional land use reviews, environmental and ecological studies, as well as a cultural and environmental monitoring program that will continue throughout the mine’s existence, says Grier.

Australian mining company Riversdale Resources, which is spearheading the project, boasts letters of support from all five Treaty 7 nations — Piikani, Kainai (Blood Tribe), Siksika, Stoney Nakoda and Tsuut’ina — as well as the Métis Nation of Alberta Region 3 and the National Coalition of Chiefs.

But Calf Robe says this support is superficial.

She says while companies have a duty to consult with impacted First Nations, it often involves them simply telling leadership what they’re going to do.

“The duty to consult does not equal community-level consultation. It does not equal consent from members of the Blood Tribe,” she said, adding that members of other Treaty 7 nations have expressed similar frustrations.

Adam North Peigan of the Piikani Nation is one.

“The Chief basically made a statement and not only did he put his name on the line, but he put the entire membership and dragged our name through it as members,” said Peigan. “We take offence to that, because our thoughts are that at the outset there was no meaningful consultation with grassroots members.”

He says any consultation with Piikani must have been done with the Chief and council “and that’s where it stopped.”

Noticing a backlash towards the Chief’s statement on social media, Peigan set up a forum on Zoom for band members “to come forward and talk about their frustrations and their reasons and their feeling and their thoughts on why they felt that this Grassy Mountain coal mine project in Crowsnest Pass was an endangerment to the environment of the traditional territory of Piikani.”

“There was a lot of enthusiasm coming out of that discussion,” he said, adding that they scheduled another meeting for the following week.

First Nations communities are generally bereft of the resources to do their own independent research into the impacts of resource extraction projects, but one can look towards the B.C. side of the Rockies for the impact of open-pit mining on their water supply, Calf Robe explains.

“Those messages of ‘Coal is good, coal is clean’ is all that’s provided to First Nations communities,” said Calf Robe. “We’re always stretched to the bandwidth … Nobody has the time or effort to spend money on testing the quality of water.”

This dire economic situation makes First Nations leadership more willing to accept harmful resource extraction projects in the name of job creation, she added, pointing out the average annual income on Blood Tribe is about $20,000.

Peigan said it’s the same issue on Piikani, adding that there’s probably an element of each nation not wanting to be “left out in the dark” while the neighbouring nations reap the benefits of employment.

“We need jobs in our communities, but these aren’t the types of jobs we need,” said Calf Robe.

(Disclosure: This writer is a co-host of the Forgotten Corner Podcast.)

Be the first to comment on "Coal policy reinstatement doesn’t impact planned Grassy Mountain mine"