by John Copley

(November 11, 2017) – These days, heroes are found flying across movie screens, battling aliens in video games, and punching out villains in the pages of comic books. But in reality, heroes have been defending our freedoms for a very long time.

“Zinging bullets, the crashing sounds of cannon-fire, muddy trenches, miles of barbed wire and bodies strewn across the landscape; war is indeed little more than hell on earth,” assures 83-year-old veteran John McDonald. “Over the years I have spoken with and worked with many Indigenous veterans. Those who made it back from the wars were proud of their participation, sorry for the losses of their friends and fellow soldiers, and all with words that praised the comfort of peace and offered prayers that the world would see no more war.”

Recipient of the Canadian Forces Decoration with two bars, McDonald served for 31 years as a member of the Royal Canadian Artillery and Royal Canadian Electrical Mechanical Engineers, and another eight in the Reserve. Today, as the president of the Aboriginal Veteran’s Society of Alberta, he assists those in need in addition to being a recruitment coordinator with the Canadian Forces’ Bold Eagle Program.

Veteran John McDonald is the recruitment coordinator for the Bold Eagle Program.

Indigenous people who served their country did so for a variety of reasons,” explains McDonald. “Some just wanted the opportunity to participate, to work, to leave the reserves they felt trapped on. Others wanted to honour their ancestors and to follow in the footsteps of their uncles, fathers and grandfathers. Indigenous people proved to be natural soldiers – they were skilled shooters, stealthy movers, experts at camouflage and fearless fighters.”

Indeed, for more than a century, thousands of Canadian Indigenous soldiers, sailors and air force members have participated in conflicts across the globe, including the Boer War, World War I and II, and the Korean War. They have also been among the most celebrated.

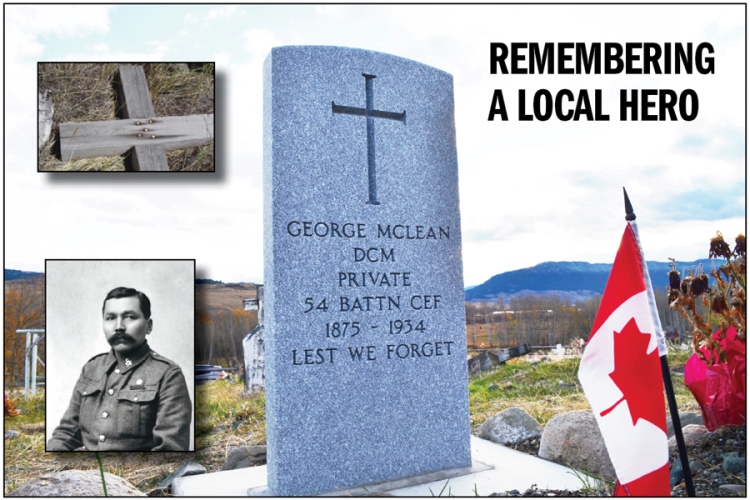

During World War I, Indigenous soldiers earned at least 50 decorations for bravery. Among them was Private George McLean, a member of British Columbia’s Head of the Lake Band, who fought at the Battle of Vimy Ridge in the 54th Kootenay Battalion. The book, Native Soldiers: Foreign Battlefields, notes: “Single-handed he captured 19 prisoners, and later when attacked by five more (enemy soldiers) who attempted to reach a machine gun, he was able – although wounded – to dispose of them unaided, thus saving a large number of casualties.”

Others include Henry Louis Norwest, an Alberta Métis soldier and one of the most famous snipers of the entire Canadian Corps. He held a divisional record of 115 fatal shots and was awarded the Military Medal and bar for his courage under fire. Francis Pegahmagabow, an Ojibwa from Ontario, was another top sniper and to this day remains Canada’s most decorated Indigenous soldier.

Others include Henry Louis Norwest, an Alberta Métis soldier and one of the most famous snipers of the entire Canadian Corps. He held a divisional record of 115 fatal shots and was awarded the Military Medal and bar for his courage under fire. Francis Pegahmagabow, an Ojibwa from Ontario, was another top sniper and to this day remains Canada’s most decorated Indigenous soldier.

World War II also witnessed extraordinary feats of courage and stealth. A member of the Brokenhead Band in Manitoba and descendant of Saulteaux Chief Peguis, Tommy Prince was recruited into the 1st Special Service Force (1st SSF), a renowned assault team known by the enemy as the “Devil’s Brigade.” As the Canadian Encyclopedia recounts:

Sergeant Tommy Prince

“Prince distinguished himself with the 1st SSF in Italy and France, using the skills he’d learned growing up on the reserve… In February 1944, he volunteered to run a communication line 1,400 metres out to an abandoned farmhouse that sat just 200 metres from a German artillery position. He set up an observation post in the farmhouse and for three days reported on German movements via a communication wire.

When the wire was severed during shelling, he disguised himself as a peasant farmer and pretended to work the land around the farmhouse. He stooped to tie his shoes and fixed the wire while German soldiers watched, oblivious to his true identity. At one point, he shook his fist at the Germans, and then at the Allies, pretending to be disgusted with both. His actions resulted in the destruction of four German tanks that had been firing on Allied troops.

In France in the summer of 1944, Prince endured a gruelling trek across rugged terrain to locate an enemy camp. He travelled without food or water for 72 hours. He returned to the Allied position and led his brigade to the German encampment, resulting in the capture of more than 1,000 German soldiers.”

For his selfless acts, Prince was decorated with the Military Medal personally by King George VI at Buckingham Palace. He enlisted again in the Korean War and, as a member of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, was awarded the United States Presidential Unit Citation for distinguished service. He would also personally receive Korean, Canadian Volunteer Service and United Nations Service medals.

Veteran Don Langford is executive director of Metis Child and Family Services and an Elder at Amiskawaciy Academy in Edmonton.

“Indigenous soldiers,” observes Métis Elder and 37-year veteran Don Langford, “were elite fighters throughout the various wars and conflicts they’ve participated in. More important is that they returned home with a great deal of knowledge and leadership abilities.”

Some of these include Sam Sinclair who played a major role in developing the Métis Nation of Alberta, Stan Shank who helped create Native Counselling Services and the Canadian Native Friendship Centres, Vic Letendre who developed Native Youth Justice Society, and Lt. David Greyeyes who returned home to become Chief of his Band, a director with Indian Affairs and a Member of the Order of Canada. As Langford notes, “The list goes on.”

Langford, the executive director of Edmonton-based Métis Child and Family Services, himself served in five different Canadian Forces bases as well as in Germany. He was one of about 30 serving members who lobbied for greater Indigenous rights and to create opportunities for young Indigenous Canadians in the military.

“It was about 16 years ago when Canada’s Armed Forces recognized the contributions by Aboriginal soldiers, sailors and airmen,” says Langford. “They now allow First Nations servicemen to wear their braids and, more recently, the Métis to wear their sashes. Aboriginal veterans are also allowed to wear their Aboriginal War Medal, which was created about a decade ago.”

The actual number of Native Canadians who participated in the two World War campaigns is not actually known. Accurate records weren’t kept and many Indigenous peoples, including the Métis and the Inuit who were not included in the Indian Act didn’t qualify for the tally sheets that included First Nations soldiers. The number however was high. During the First World War alone, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs, one in three Indigenous men who were of age to serve enlisted to defend their country.

Today, members of Canada’s Armed Forces continue to protect the nation’s interests, and are involved in everything from territorial surveillance and assisting with natural disasters to serving as peacekeepers and providing humanitarian assistance. Indeed, there is no reason to look up to the sky for a hero. We simply need to look around us.

This article was originally published in Syncrude Canada’s Pathways Publication.

Be the first to comment on "Saluting the important contributions of Indigenous veterans in Canada"