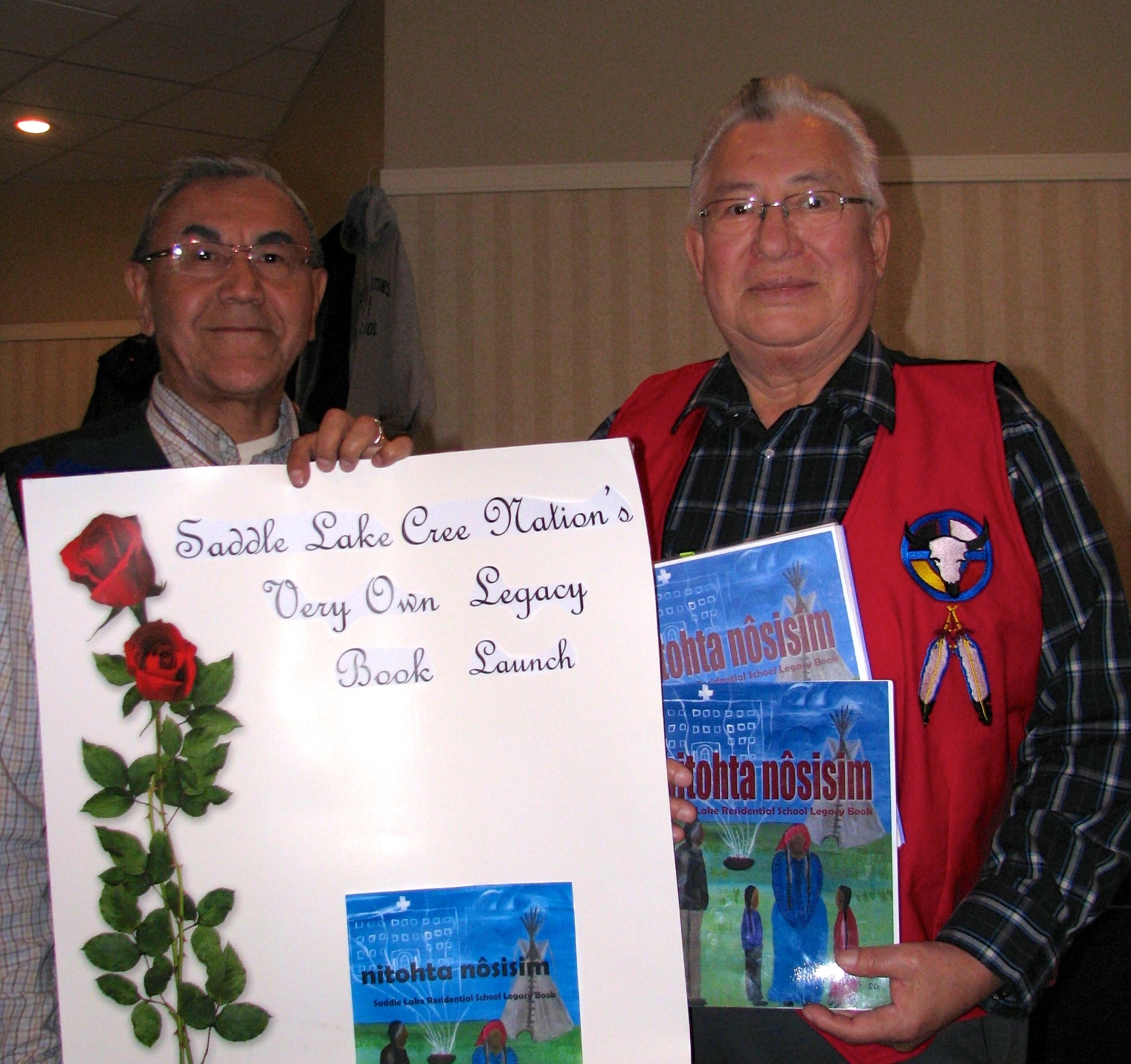

On November 27, the Saddle Lake First Nation Indian Residential School (IRS) Office launched its newly published Legacy Book, nitohta nosisim (Listen My Children). The launch, which took place during the recent three-day Knowing Our Spirits Conference at the Ramada Edmonton Hotel, fulfills the goal of the community’s IRS office to create a book that can be utilized within the community schools, libraries and homes.

“This important undertaking,” noted Eric Large, a contributor in the book and a Saddle Lake Cree Nation IRS Office health support worker, “has been realized; nitohta nosisim will be used in the schools and in the community to help ensure that the memories of those days are never forgotten and that our youth and community members know the truth about the Indian Residential Schools and their impact on us as a people.”

The book is comprised of interviews with nine former residential school students, including Jenny Cardinal, Mary Cardinal Collins, Dorothy Visser, Nathaniel (Big Dan) Cardinal and others, each of whom attended either the Blue Quills Residential School or the Edmonton Indian Residential School. It will be used to provide a platform for advocacy, education, healing and reconciliation. The glossy covered 119 page book also highlights a gallery of colourful photographs, various documents and an introductory preface by Eric Large.

Well known and respected Elder and businessman, Charles Wood, was born in a log house on the second of May 1938. A former Blue Quills residential school student and one of the nine contributors in the book, the 78 year old survivor joined Large at the Ramada to showcase the new Legacy Book.

“My father attended at residential school in the early 1990s when they were called Industrial Schools,” he writes in his memoir. “I think with all that he experienced he did not want me to be exposed to that. He held back as long as he could. I remember the time, one day in the month of February, an Indian agent arrived at our house with an RCMP officer. I did not know what was being talked about because I did to understand English; I only spoke Cree. My parents were threatened that if they did not bring me to school immediately, that my father would be picked up and incarcerated. I remember the long bumpy ride.”

In an interview Wood elaborated, “It is important that this Legacy Book be read and interpreted for what it is; stories from and about real people, who were victimized in one way or another by the Indian Residential School system and what it stood for. We need to be certain that our youth know the truth about what happened so they in turn can learn more about themselves; by telling our stories we can heal and move on and overcome the atrocities of those days.”

“I am hopeful that this is just the beginning,” mused Eric Large. “I can see where this Legacy Book can be used as a template for other communities to put together their own book. If that is the case then we will help them to do that.”

The book, was created simultaneously with a uniquely designed teacher resource guide. It will be provided to students in kindergarten to grade nine in the schools in Saddle Lake “so they can learn what their ancestors were taught at a residential school setting.”

The project got underway after funding was secured through the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement’s Commemoration component. Funding from the Commemoration initiative must be used to support regional and national activities that honour, educate, remember and/or pay tribute to former Indian Residential School (IRS) students, their families and their communities.

After workshops, gatherings and meetings between school and cultural support workers it was decided by the community to go ahead with the Legacy Book project. Rather than host a two or three day workshop or conference, a more lasting project was initiated, one that would commemorate former residential school students.

“When the funding was approved in 2011,” noted Large, “Saddle Lake members Valerie Cardinal and Martha Half were engaged to provide research and to interview Indian Residential School former students from Saddle Lake. A number of family names were interviewed to represent families and clans. Due to limited funding we could not interview everyone affected by the schools.”

Nitohta nosisim’s (Listen My Children) accompanying teacher resource guide was developed, designed and written by community members and school teachers. Valerie M. Cardinal wrote the lesson plans for students in Kindergarten through Grade 9, while Pam Brertton, Tori Beth Jackson, Bruce McGilvery and Jackie Steinhauer did the same for Grades 6 to 9.

The Indian Residential School experience, legacy, and impacts are varied and can be complex. Among other things, it can involve any aspect of trauma, associated anxiety, impact on relationships, spouse, children, and grandchildren and impact on the former student’s community. Up to now, there is a scarcity of research findings that confirm ether direct or indirect links between the Indian Residential School experience(s) and effects on former students, their descendants, relationships, or their communities. “Perhaps there could be further research of the various effects and this book could be revised or expanded to include general and specific elements of knowledge of the Indian Residential School experience and its impact,” suggested Large. “It is very important that our Native peoples record and transmit knowledge that is Indigenous to us and are able to retain and interpret that knowledge according to our worldview and interests.”

The $20 million distributed via the Commemoration funding initiative reached out to 145 different projects across Canada and was based on recommendations from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Commemoration is jointly managed by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The TRC’s role was to receive and review proposals to ensure they met the program objectives, as set out in Schedule J of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement and then make recommendations to AANDC for funding, who would then fulfil its role by approving and funding projects recommended by the TRC.

The goals of the Commemoration component within the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement included assisting in honouring and validating the healing and reconciliation of former students and their families through Commemoration initiatives that address their residential school experience; to provide support towards efforts to improve and enhance Aboriginal relationships and between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people; to provide an opportunity for former students and their families to support one another and to recognize and celebrate their strengths, courage, resiliency and achievements; to contribute to a sense of identity, unity and belonging; to promote Aboriginal languages, cultures, and traditional and spiritual values; to ensure that the legacy of residential schools and former students and their families’ experiences and needs are affirmed; and finally, to memorialize in a tangible and permanent way the residential school experience.

by John Copley

Need to know where I can get a copy of this book, it’d b nice to know a lil more about my father, Charles

Thanks for the question Charles. We’ll try and find out for you.

Hi, where can I find more information on this book?

I would like to get a copy of this book, I had no idea of the atocyties committed against the natives in these schools. It sounds similar to what was done and n the Naxi death camps. My heartbreaks for these children that suffered at the hands of the Catholic, Anglican and United Churches. These stories must be told and never forgotten.