by John Copley

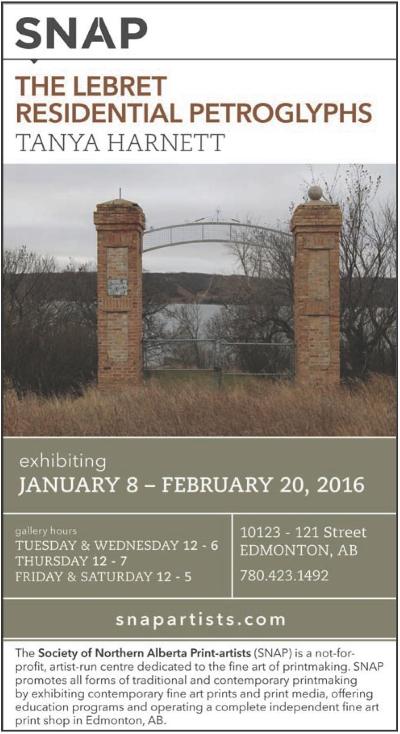

(ANNews) – Tanya Harnett’s newest display of artistic creation is currently on exhibit at the SNAP Gallery in Edmonton. Her current work, The Lebret Residential Petroglyphs, is a series of photographic prints that helps confront and explore the devastating impacts of Canada’s Indian Residential School system.

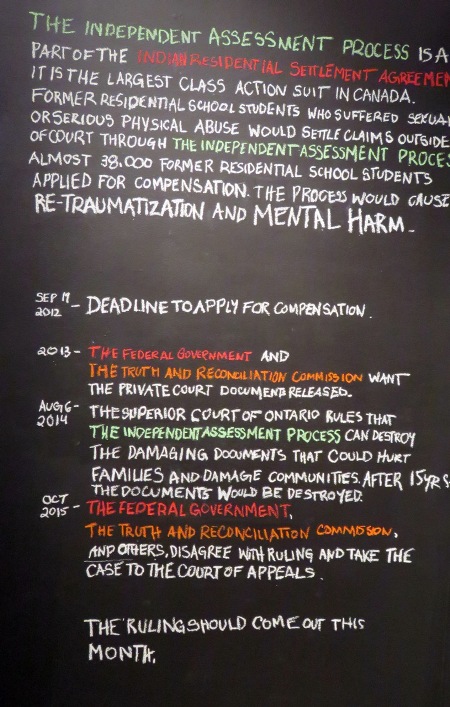

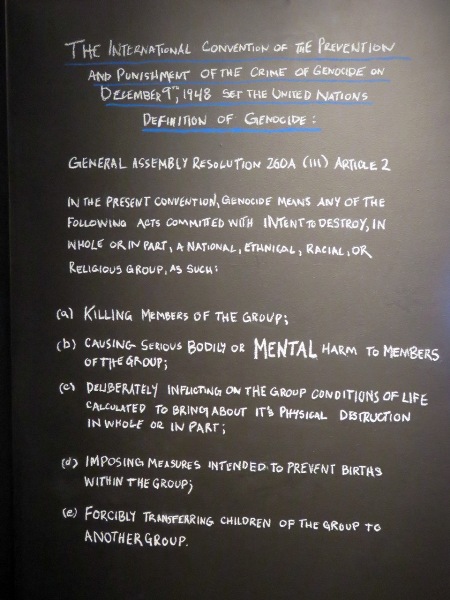

The exhibit, which runs at the SNAP Gallery until February 20, 2016, takes on two distinct shapes. The first includes a chronological (1998-2015) series of chalkboard writings that highlight the years and pinpoint a timeline that begins with the creation of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation in 1998 and concludes with Supreme Court of Canada Chief Justice Beverly McLachlan’s referral to Canada’s treatment of Indigenous peoples as ”cultural genocide.”

The second features numerous photographs taken by Harnett on her visits to the old Lebret residential school site in Saskatchewan.

A daunting slogan, Gateway to Hell is inscribed on the gate leading into the old Indian Residential School at Labret, Saskatchewan.

The exhibit is reminiscent of her Scarred and Sacred Waters series that was developed from her visits to various First Nations where the quality of water is under distress from subterranean oil and gas exploration. Even more compelling than that series, but with the same educational value and constructive awareness, The Lebret Residential Petroglyphs highlights the plight of a people. It provides insight into the horrific story of residential school abuse by offering proof and asking wise and credible questions. Harnett’s creative exhibit is not designed to keep negativity and mistrust in the forefront, but instead to bring awareness to the Canadian public, to challenge the legality of commitment, to honour a people who suffered unimaginably at the hands of politicians, bureaucrats, church officials and government propaganda for more than 200 years.

The residential school exhibit features a series of explanative black slate chalkboards created via a colour chart – red, blue, yellow, green, orange – each with its own significance. Although the exhibit was not created as a testimony to the many years it took for the TRC to complete its mission, nor is it designed to command attention to the 94 recommendations that came about as a result of the TRC’s seven year investigation – though those things are both at the top of the artist’s agenda when it comes to concerns about the future.

The residential school exhibit features a series of explanative black slate chalkboards created via a colour chart – red, blue, yellow, green, orange – each with its own significance. Although the exhibit was not created as a testimony to the many years it took for the TRC to complete its mission, nor is it designed to command attention to the 94 recommendations that came about as a result of the TRC’s seven year investigation – though those things are both at the top of the artist’s agenda when it comes to concerns about the future.

“There are few messages but many questions in this particular set of panels,” noted Tanya Harnett. “The biggest question I have tried to ask here – is why is the TRC and the federal government, namely the Department of Indian Affairs, trying to overrule a court approved decision in favour of the Independent Assessment Process – a process that has already set in place a plan that will seal the records of more than 30,000 residential school claimants and then see them destroyed after a period of 15 years.”

More than 6750 victims and survivors who filled out the disparaging application forms have agreed to share their stories; the others have not. The application forms make it clear that ‘confidentiality’ is guaranteed – these are contracts between victims of abuse and those seeking answers about that abuse. This case should come before the court again this spring and Harnett’s newest exhibit could help get the court of public opinion involved before it does.

“There are questions that need answers, no doubt about that,” she said. “Hopefully wiser heads will prevail and someone will realize that the words and anguish and memories of nearly 7,000 should be enough to get the message across; there is no need to destroy more lives, relive more bad memories or break yet another agreement by betraying the confidence of those who came forward to tell their stories – in confidence.”

The 20 page questionnaire is indeed a ghastly and poorly orchestrated form that is a bit difficult to understand, exceptionally demeaning and demands that victims account for every sordid detail of their experiences in the schools. That’s a story for another day.

Tanya Harnett is an artist and an educator – not a politician. You won’t see her standing at the podium waving or raving or demanding justice. She takes photographs and they are her truth.

Her latest exhibit includes a series of photographs taken at the now demolished residential school at Lebret Indian Residential School. Formally known as the Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School or Qu’Appelle Industrial School and then Lebret Residential School, the facility was financed by the federal government. It operated from 1884 to 1969 under Roman Catholic guidance. It was run by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate and the Grey Nuns on what is now the Wa-Pii Moos-toosis (White Calf) Indian Reserve of the Star Blanket Cree Nation. It adjoins the village of Lebret, Saskatchewan, which is located on the northeast shore of Mission Lake in the Qu’Appelle Valley six kilometres east of Fort Qu’Appelle.

Harnett has personal interest in this particular venture; her great grandfather and grandmother both attended the school. Her own mother was sent to the residential school in Brandon, Manitoba – as were many of her family members. Most have since passed on, some through personal trauma and others through disease such as tuberculosis. Her great grandfather, Ochankuga’he, or Path Maker as he was later named, was sent off to residential school at a very young age.

In his book, “Recollections of an Assiniboine Chief” he wrote, “In 1886, at the age of 12 years I was lassoed, roped and taken to the government school at Lebret. Six months after I was enrolled, I discovered to my chagrin that I has lost my name….”

The book, published in 1972, was written under that new name: Dan Kennedy. They cut his braids and he ran away. He was caught and he ran away again.

“I made two more attempts,” he wrote, “but with no better luck. Realizing that there was no escape, I resigned myself to the task of learning the three R’s.”

The book delves into many stories and tales about the past and offers personal accounts of knowledge surrounding the Cypress Hills massacre. A rare book and out of print, “Recollections of an Assiniboine Chief” is a collector’s item for anyone who manages to find a copy. It’s a great read – but again, a story for another time.

Harnett didn’t have a lot to work with when she decided to create her pictorial of the Lebret school because the only thing still standing is the front gate.

This gate is all that remains of The Lebret Indian Residential School, in the Qu’Appelle Valley of Saskatchewan. The school was closed in 1969.

“It’s a daunting, even haunting feeling to see that gate standing there all by itself,” she said. “I used to play around there when I was a kid and I had no idea what it was or what it meant. To see it today is to remember the past and those who suffered behind the concrete walls and under the thumb of administrators and government officials whose main purpose was to destroy the individual’s sense of identity through a series of punishments that not only wreaked havoc on an entire culture, but in the process destroyed human beings in the worst imaginable ways.”

That’s why, Harnett noted, that she is intent on getting her message out to every Canadian who wants to know the truth and wants to see justice prevail.

“That justice,” she said, “begins with the implementation of the 94 recommendations that came about as a result of the TRC’s Final Report. It doesn’t end there, but it’s a great place to start.”

The inscriptions on the single gate that remains at Lebret are symbolic of the feelings and experiences shared by the thousands of children who made their way through the school for more than 85 years. “Gateway to Hell” is the one inscription that says it all.

There are many topics that accomplished artists can share with society, so when an opportunity presents itself to an artist who wants to ensure that truth supersedes all else, it is difficult to turn away an invitation to create a piece of work that helps Canadians become better aware of what was and is going on in Canada, particularly when it comes to Indigenous peoples. To correct the future we must understand and deal with the past.

Tanya Harnett is a Nakota artist from Saskatchewan’s Carry the Kettle First Nation. She moved to Stony Plain as a young child and remains close to her family in Saskatchewan. A former University of Lethbridge professor, she currently teaches Native American Studies at University of Alberta with a joint appointment in the Department of Art. She has also taught courses at Grant MacEwan University.

The Society of Northern Alberta Print-artists (SNAP) is a not-for-profit, artist-run centre, and a registered charity incorporated under the Societies Act of Alberta. Since its inception in 1982, SNAP has grown to become one of Canada’s premier centres for research and innovation in printmaking as well as providing a unique forum for discussion and examination of critical and theoretical issues related to printmaking and image culture.

Be the first to comment on "Lebret Residential Petroglyphs on display at SNAP Gallery in Edmonton"