by John Copley

(ANN) – Landmark: A New Chapter Acquisition Project (April 28 – Nov. 11) is the latest in an exciting series of Art Gallery of Alberta (AGA) exhibitions taking place now through 2019. This new Landmark presentation is the second in a series of exhibitions supported by a Canada Council for the Arts “New Chapter” grant, an initiative that enables new acquisitions to the AGA’s permanent collection of work by Indigenous, Métis and Inuit artists to be showcased and presented to the public.

The Canada Council for the Arts’ New Chapter program utilizes its $35 million investment by supporting the creation and sharing of the arts in communities across Canada; Landmark is one of the 200 important projects funded through the initiative. This latest exhibition features new work by three well-known Indigenous artists from Alberta – Tanya Harnett, Terrance Houle and Brenda Draney.

Executive Director and Chief Curator of the Art Gallery of Alberta, Catherine Crowston, told Alberta Native News that “the AGA is thrilled to be presenting the second in a series of exhibitions that feature the work of contemporary Indigenous artists. The three artists in this exhibition are all from Alberta, and each has made significant contributions to the cultural landscape of the province. It is even more important that these works have been added to the AGA’s collection, making them a legacy for generations to come.”

“I am so very delighted to have had my work chosen for this unique Landmark exhibition,” smiled artist Tanya Harnett, who said she was pleased that Albertans and visitors to the province would now have even more opportunity to see her work and absorb the messages she’s left in her wake.

Wabamum Lake- an edited photo by Tanya Harnett that demonstrates the damage done to mother earth.

Harnett’s contribution to the current AGA Landmark exhibit is her six-piece photo series entitled Scarred/Sacred Waters, a unique and important piece of work produced in 2011. The collection has travelled the world and has been lauded by audiences across the globe for delivering an important message for all nations to heed. The work has been showcased in numerous countries and locations including Canada, Great Britain, Japan and Hungary. One of the first to exhibit the work was the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford University and later, Aberdeen University in Scotland.

“There’s always been a lot interest in the Scarred/Sacred Waters series,” noted the artist. “It doesn’t matter what part of the world you live in and it doesn’t matter what culture you come from or how much money you make, everyone is concerned about polluted waters, decimated landscapes and human health.”

The Scarred and Sacred Waters series was created during Harnett’s travels across the actual landscape, particularly to land occupied and utilized by Indigenous peoples. During its first exhibition in 2011 the series declared that environmental distress in First Nations communities “is a direct result of Canada’s earliest history and how immigration redistributed the land into illogical measured areas, especially to nomadic people. The effects of how we as humans operate in the contemporary world have repercussions that follow no marked-out boundaries. Harnett’s interventions into the water sources belonging to Indigenous reserve lands carry a subtle message that is not only aimed at an answer, but more compellingly, towards the question.”

Tanya Harnett reflects on the message she delivered in her Scarred / Sacred Water Series.

That question, she said, is multi-faceted and begins with a statement.

“Environment is a real issue and it needs to be talked about; it needs to be protected. Industry needs to work smarter and safer. The environment is a subject that needs to be talked about and trying to stifle the conversation by acts such as protesting the University of Alberta for wanting to honour a person such as David Suzuki is counterproductive to progress.”

Water, assured Harnett, is mankind’s most precious commodity and the one thing that needs to be protected against every possible malady.

“We need to use energy smarter; we are an energy producing province and yes we need the oil – but we can work more efficiently, be more effective and more environmentally conscious. We especially need to do more to protect our water because barrel-to-barrel, water is worth twice as much. We cannot survive without it. As a province we need to diversify; we shouldn’t have to depend on one product to produce the revenues needed to sustain a population.”

Gallery Attendant Paul Blinov is a great communicator who is most helpful in discussing the essence of the artwork and some of the messages each piece delivers.

The second of the three artists whose new work is being showcased in the Landmark: A New Chapter Acquisition Project is interdisciplinary media artist, Terrance Houle, a resident of Calgary and a member of southern Alberta’s Kainai Blood Nation.

Unable to contact Houle, I defer to the explanation of his work by AGA Gallery Attendant Paul Blinov.

“Ghost Days: Indian Graves is the first of two Terrance Houle pieces on exhibit here today,” explained Blinov. “To capture this three-piece photo series the artist visited several burial sites; he didn’t photograph the actual burial site but instead took it from the site – looking up as if trying to capture the scene looking from the ground to the sky, perhaps toward the spirits and the Creator.”

Ghost Days is a unique four-photo light-jet series enhanced with an array of multi-toned special effects.

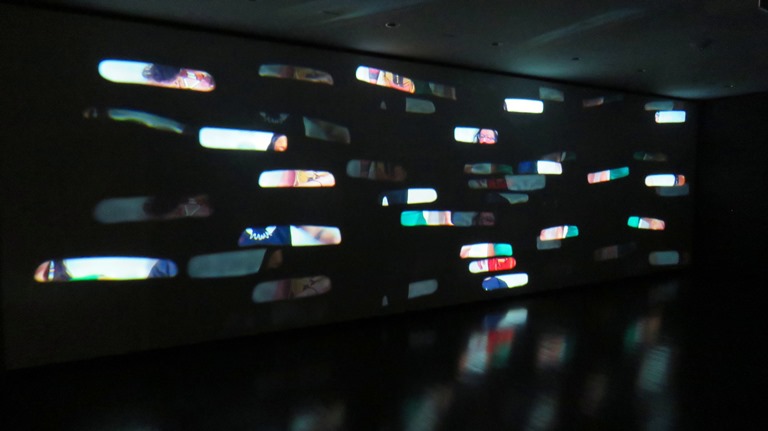

Terrance Houle’s second exhibit, Your Dreams Are Killing My

A series of mirrors reflect light signals to an adjacent wall where the colours form an unusual but attractive piece of art.

Culture, is another unique piece of art. The first of the two pieces presents a series of what appears to be used mirrors from the interior of automobiles. Each mirror is attached to a single four foot by two foot board. The mirrors reflect light signals that emit from a video camera in the ceiling to an adjacent wall where the colours form an unusual but attractive piece of art. The second part of the exhibit is the interior gallery wall that presents disfigured reflections from the mirrored light in an unusual and ever-changing pattern of colours and images.

Houle lives and works in Calgary, and travels to reservations and Indigenous communities throughout North America to participate in powwow dancing and ceremonies. He is a graduate of the Alberta College of Art and Design and has exhibited in Canada, the United States, Australia, the UK and Europe. In 2004 he received the award for Best Experimental Film at the Toronto ImagineNATIVE Film Festival and in 2006 he received the Enbridge Emerging Artist Award.

The third of the three artists represented in the Landmark series, Brenda Draney, is a member of the Alberta’s Sawridge First Nation. A recipient of the Eldon and Anne Foote Visual Arts Prize in 2014, Draney, who was educated at both Vancouver’s Emily Carr University (MA in Painting) and Edmonton’s University of Alberta (BA Education; BA Painting) lives and works in Alberta’s capital.

Capturing winter….an unnamed piece of art by Brenda Draney.

Draney’s unnamed exhibit comprises a series of paintings that at first glance appear to be unfinished and mounted to the gallery wall in error, but that illusion is quickly diminishes when one looks beyond the paint and into the canvas itself. It appears to be empty when in fact it is just devoid of paint.

“It’s for you, the viewer, to decide what each painting means,” chuckled Draney upon being asked if the engine of the single-car locomotive in her art represented a close call she’d had at one time or another with a train. “What do you think it means?”

The white space that dominates Draney’s seemingly unfinished canvases is not empty at all; it is for the viewer to fill in by mixing what the eyes see with a bit of imagination and a personal experience that has significant meaning. In one painting a man, clothed in something familiar yet foreign (conquistador clothing?) is tied to a tree; a tent stands behind him to the right – little other colour fills the canvas but it does appear like wintertime with the wind about to sweep in.

“Brenda’s work is unique, seems to be unfinished, even dream-like in that we see little pieces but maybe not the whole story,” Blinov noted as we discussed her work. “For example, as a child she would play a game where the children would run around and tie each other up to trees; this is sort of based on that memory but the person in this picture looks more like an adult so maybe there is something else going on that we don’t know about.”

Visions, recollections and viewer connections are all embraced in Brenda Draney’s art

In another painting a man leans forward over the bumper of a dark grey truck; he’s in a standing-shooting position aiming down the road at an unseen target with an imaginary rifle clasped in his grip. It’s a bright summer day, the sky is blue and there’s white-fronted structure standing in the background. Could it be a chicken coop just robbed by a local fox or coyote with a would-be shooter wishing he had a real gun? Is it hunting season with a deer walking down the brush-line and a hunter caught unaware and unarmed?

“You have done exactly what I hope that every viewer of this work will do,” assured Draney when I related what I’d glimpsed in her various offerings. “That is the whole idea behind this art: you decided it was a conquistador; you decided it was winter; you decided it was a chicken coop. You generously brought your own history, stories and ideas and informed all of these art pieces with your own stories, ideas and history. We had ourselves a little dialogue, a little conversation and that’s at the generosity of your’s, the viewer, and I really appreciate that.”

Draney noted that when growing up as a child “stories were so important, so fun and so informative. It’s how I learned about my family, my community, my culture. Kitchen tables, fire pits and everywhere people sat or gathered – they were all important. Stories are neat and they aren’t always remembered the same way. For example, I’ve discussed memories from a past Christmas with my sister and discovered that we didn’t remember it the same way. We all have our own interpretations of things and that’s why when you walk by this artwork it’ll tell you thousands of stories – and that’s the fun part because what we, as individuals see in the work, is what is meant to be seen.”

The AGA’s exciting Landmark Series: A New Chapter Acquisition Project runs until November 11. Be sure to visit this unique collection of work. For more information visit youraga.ca.

Be the first to comment on "AGA exhibit features three prominent Indigenous artists"