By Regan Treewater

(ANNews) – February 14 was an uncharacteristically warm night here in the City of Champions. The roads were filled with slush and muck — but that did not deter a crowd of passionate First Nations activists and local community members from taking to the streets in solidarity for the missing and murdered women and children of Canada. Young and old, women with bundled newborns in tow, and even those not personally effected, united for the sole purpose of demonstrating that Canadians, of all backgrounds, will no longer turn a blind eye to major violations of basic human rights within our own borders.

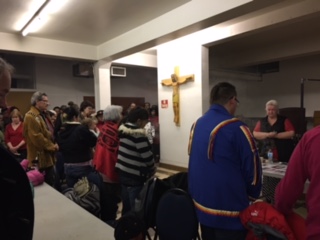

In the basement of Edmonton’s Sacred Heart Church of the First People, row after row of long sprawling tables filled a dimly lit room. Within a half hour the large space was completely packed with standing room only and a crowd of people huddled outside craning their necks to listen through the open door. “This affects everybody,” explained a tired looking middle-aged woman while fixing her hair in front of the bathroom mirror, “it’s an everybody problem, it’s just that nobody knows about it.” She politely declined to have her name appear in print, but began to count — first on the fingers of one hand, then on the fingers of the other — how many women in her family had gone missing or been murdered.

In the basement of Edmonton’s Sacred Heart Church of the First People, row after row of long sprawling tables filled a dimly lit room. Within a half hour the large space was completely packed with standing room only and a crowd of people huddled outside craning their necks to listen through the open door. “This affects everybody,” explained a tired looking middle-aged woman while fixing her hair in front of the bathroom mirror, “it’s an everybody problem, it’s just that nobody knows about it.” She politely declined to have her name appear in print, but began to count — first on the fingers of one hand, then on the fingers of the other — how many women in her family had gone missing or been murdered.

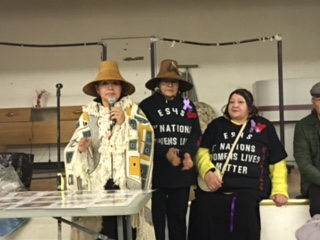

Gladys Radek was guest speaker at the Edmonton Walk for Missing and Murdered Women held on Feb. 14, 2017.

In 2006 Danielle Boudreau was the initial visionary of the Edmonton Walk for Missing and Murdered Women. Before the opening prayer, she tearfully announced that this would be her last year leading the effort. She was joined by her mother, Linda Boudreau Semaganis and members of the local non-profit Edmonton Sisters4Sisters, founded by Cynthia Rattlesnake Cardinal and her sister Bonnie Fowler. Cardinal and Fowler first established their group to commemorate the memory of their sister Georgiana Faith Papin who was a victim of the notorious serial killer, Robert Pickton. They remain committed to supporting other families who have had mothers, sister, wives and daughters silenced by violence. “It’s genocide,” announced guest speaker Gladys Radek, “what better way to do it than to kill our women – the givers of life!”

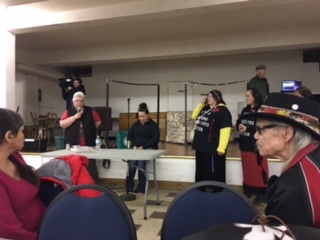

The keynote address was a delivered by Walk for Justice organizer Bernie Williams.

The keynote address, delivered by activist and Walk for Justice organizer Bernie Williams, served as a haunting reminder that it is our own mainstream society that has long neglected the needs of First Nations women in particular. “I was sold into sexual slavery at the age of eleven,” Williams revealed to the sizeable crowd. She went on to explain that marginalized communities are not only victimized by, what she termed “colonial powers,” but also by more insidious offenders like addiction and poverty. She cited fentanyl laced drugs as the most current and prolific murderer of Indigenous people.

The procession to Churchill Square in downtown Edmonton.

Longtime local residents of the surrounding area, both First Nations and not, shared stories about seeing the same women walking their street corners for months, only to one day find them absent. This reality is corroborated by Rosvita Dransfeld’s 2012 documentary film Who Cares. The footage, all shot in close proximity to the Sacred Heart Church, chronicles the ongoing efforts of Project KARE, an RCMP initiative to help identify the recovered bodies of murdered women. Although the project continues to provide important closure for grieving families, one cannot help but wonder if more can’t be done to prevent such disappearances before the fact.

The procession, which snaked its way from the inner-city McCauley area, past the police station on 103A Avenue, looping around at Churchill Square, seemed to grow as the march progressed. A formidable police escort lined the entirety of the route — the lights atop their vehicles strobing colourfully. During her opening remarks, Danielle Boudreau told gatherers that in past years Edmonton Police had kindly volunteered their services to ensure the group’s safety. She noted this as a significant cooperative collaboration between First Nations and law enforcement, two groups that have long harboured mutual animosity and mistrust. Marchers came out in full force brandishing drums and homemade banners all to show their collective support. “When you walk away, you don’t walk away the same as when you came in,” Semaganis announced with conviction.

The procession, which snaked its way from the inner-city McCauley area, past the police station on 103A Avenue, looping around at Churchill Square, seemed to grow as the march progressed. A formidable police escort lined the entirety of the route — the lights atop their vehicles strobing colourfully. During her opening remarks, Danielle Boudreau told gatherers that in past years Edmonton Police had kindly volunteered their services to ensure the group’s safety. She noted this as a significant cooperative collaboration between First Nations and law enforcement, two groups that have long harboured mutual animosity and mistrust. Marchers came out in full force brandishing drums and homemade banners all to show their collective support. “When you walk away, you don’t walk away the same as when you came in,” Semaganis announced with conviction.

Such events as this have gone a long way towards promoting awareness. Non-Indigenous people are gradually becoming more conscious of this persisting issue, while Indigenous people are being reminded that they do not have to remain alone in their suffering or grief. Groups like Edmonton Sisters4Sisters provide a valuable support network for families afflicted with loss, while the Edmonton Walk for Missing and Murdered Women gives a voice to victims’ loved-ones. Among these determined community leaders there is the hope that this trauma will not be the unfortunate burden of the next generation.

“To be an effective leader and a warrior you have to also be ready to be hated,” Semaganis proudly announced. But in that packed basement and along the streets of Downtown Edmonton there was nothing remotely resembling hate — everyone marched like warriors. Organizers reiterated to participants that change cannot happen overnight. But with Semaganis’ battle cry fresh in my mind as I type out these final thoughts, “we lose less, and less, and less, until we lose no more,” I think it becomes clear that with leaders like these, tragedies will not be the enduring legacy for yet another generation.

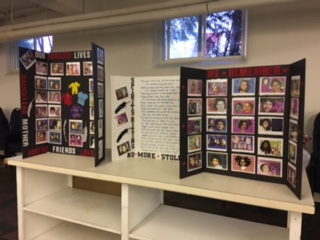

Pictures of loved ones who have gone missing.

Be the first to comment on "Marchers remember Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women"