By Dale Ladouceur, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

(ANNews) – What is the driving force that compels so many to look for anything linking us to what has gone before? Why are we driven to know our ancestors and their history? Is it more a need to belong or a need to understand why we are who we are?

Joe White and his sister Jean have felt that drive to understand their family history and to honour their father’s story for over 25 years. They were driven, in part, by the love of their father and the injustice done by a system designed to fail those it was tasked to support.

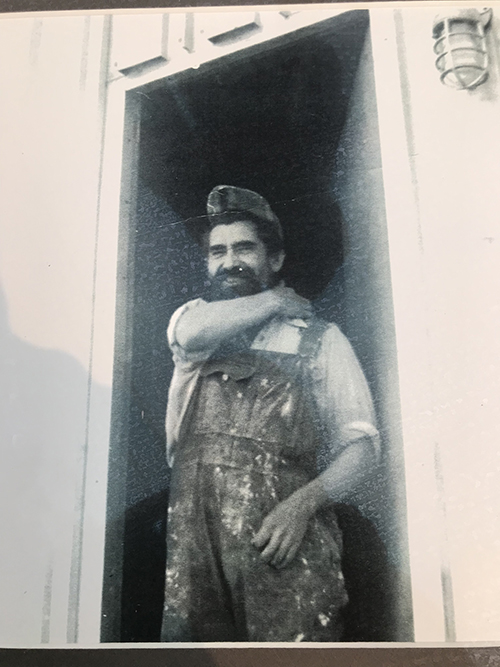

Joe and Jean White traced the history of their father Frank Joseph (pictured above) to better understand their roots. Photo supplied.

Frank Joseph was born in Fort Chipewyan in 1913. “My Dad was Dene,” Joe begins, “and that was their traditional hunting land.” In 1920 Frank Joseph’s mother died and that part of their history died with her. “Frank was taken to the orphanage, which was also the Holy Angels Residential School.”

The Dene people of the early 1900s, living around the Fort Chipewyan area were a true democracy-based community. Dene had no traditional chiefs. Whoever was the best fisher, led the fishing groups. Whoever was the best hunter, led the hunting groups. This was the community Frank Joseph White was born to: the Chipewyan Suleine.

Joe, Jean and their family were hunting for their family history, going through Fort Chipewyan records, talking to friends and relatives. Their father didn’t speak much about residential schools or WWII but that didn’t stop them from filling in the gaps.

According to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, “The Holy Angels School was founded in 1874 at Fort Chipewyan. The school moved to a new school building in 1881 which was enlarged in 1898, 1904 and 1907. A new school opened in 1944 and in the 1950s a day school operated out of the residential school. Many of the students at the school were Metis or non-Aboriginal. From the 1950s onward, Holy Angels increasingly became a child welfare institution. The school closed in 1974.”

Joe explains one of the initial hurdles his dad faced at the Holy Angels Residential School. “Frank Joseph didn’t speak Cree, he didn’t speak English and sure as heck didn’t speak French, so they didn’t have anybody that could talk to him. They would say something and he didn’t know what they were talking about so they would smack him. After getting smacked so many times he decided: ‘Well, I’m not into that’ so he would take off.”

Every time he took off Frank would go to the village and see who was around, but he would invariably get caught. Joe recalls how this piece of family history came up from Joe talking about catching grayling. His dad got caught by the RCMP following the scent of grayling over a campfire. Having nothing in his stomach, he followed the scent to a group of men cooking around a fire. Then the authorities showed up.

“The RCMP caught him and booted him in the butt – a seven-year-old kid!” Joe recalls, “You know, the RCMP steel toed boots? They booted him all the way back to the school, but he would keep running away. So, the Holy Sisters, (who were not very nice to anybody), called him the little savage boy, [and decided it was time for him to leave].”

Jean remembers it being very difficult to learn about that time in her dad’s life. “When he talked about residential schools, it was very difficult because it was a lot of stuff that he did not want to remember. That was my dad, if something bothered him, he wouldn’t acknowledge it.” Jean adds, “He did mention the Holy Angels, though. The nuns were just outrageously bad. Beating the children, feeding them rotten fish, I don’t know half the things. They were treated worse than animals. It’s just disgusting. At least animals could fight back but these little children couldn’t. I’d be very, very interested in them using the ground [penetrating radar] up in Fort Chipewyan at the Holy Angels Residential School.”

After leaving Fort Chipewyan the system sent Frank Joseph down to Fort McMurray. “There was no adult supervision,” explains Joe. “He didn’t have any papers or anything on him so Fort McMurray didn’t know what was going on. So, they put him in a place that wasn’t really an orphanage. The people looking after the kids, their name was White.” This is how Joe and Jean believe they ended up with the White surname. “We never found out until 1998,” explains Joe. “For years we were looking for information on my dad’s story but you can’t look very far when you don’t have a real last name.”

Joe tried the Catholic church bishopric up in Yellowknife and had been going through old files and remembered something that had the name backwards. “I got more info and got info on other members of the family which took two years to get recognized by the Feds as First Nations-Dene.

The Oblate brothers christened my dad the day he was born.” (An Oblate Father refers to an Oblate who is a priest, notably as a member of one of two Catholic orders).

Jean recalls the years it took to piece it all together. “The Oblates only called him Frank Joseph and only got the name White at Fort McMurray. The name missing all these years was PlateCote, our grandmother’s name. It’s not satisfying enough because we are the urban Indians, we weren’t brought up on the reserve. So, in many ways we suffered because of the disconnect.”

Joe discovered a bit of interesting notoriety in doing his research. “[Our] two great uncles, Jonas and Matisse PlatCote were the best hunters,” Joe recalls. “There was a movie made in 1919 by this HBC fellow that was called The Romance of The Northern Fur Traders and showed what they were doing, fur trapping. But there were no chiefs, you just followed the food.”

Even with the childhood he had, Frank Joseph still wanted to protect the country he lived in and lied about his age to serve in WWII. He only said two things about the war, Joe explains. “He said: ‘Funny I went through the whole war and never heard one song, (like in all these movies).” The other thing Joe remembers is that when asked if he killed any Germans, Frank would say, “I don’t know, but I sure shot at them enough.’”

Joe explained his dad was Private First Class in the Signal Core, who, [contrary to popular belief], were not behind the front lines, they were running the telephone wires to the front lines. Joe learned that Canada didn’t use wireless communications because the Germans could hear it. So, they used telephones.

Joe recalls one vivid story his father told. “They were driving in their vehicle, stringing lines and he saw a bunch of these soldiers all laying in the ditch, all huddled down. This officer saw them [in their vehicle] and said ‘What are you doing here?’ They explained they were running lines. The soldier told them they were expecting a counter attack any minute. ‘We don’t have the town, so get the hell out of here!’ He had shrapnel in him until the day he died. It was part and parcel with the war.”

Jean recalls her dad rarely spoke about his time in residential schools or the war. “He never spoke to me about the war and I think you will find that with a lot of veterans. There were certainly more than enough veterans that came from all over the North.” Jean continues, “We served well; our people didn’t back down. My dad fought to get in and served overseas, and served in the thick of things in Belgium, Holland and France.”

After the war, Frank Joseph moved to Leduc County and started a farm. Jean explained the land was given to him by the government for going off to war. “You had a choice of certain things, so he chose the farm which was a bad idea because he was only one man and you can’t be a farmer as only one man.” Jean shared that they didn’t give Indigenous soldiers returning from the war very much.

After the farm Joseph went into the oilfields and lost three fingers, as a machinist. Then he went into insulating until he retired due to Asbestosis. “He caught it in 1972 and they took him into the hospital,” Joe recalls. “They cut a third out of his lung. The doctor said to my mom he doubted he would live six more months. Well, he ended up living 15 years, which goes to show my dad was a tough old bird (laughs).”

Jean’s voice softens when she reflects on her family’s past. “I’m very sorry we didn’t get to learn any of the [Indigenous] ways. I don’t have the Dene language, which is very different than Cree. Dene was one of the languages used during the war to keep messages secret. The Japanese couldn’t break it because it’s not an easy language.”

The weight of remembrance can be heavy but the work put in by Joe and Jean White has honoured their father’s legacy. Jean’s emotions began to overtake her in sharing this last recollection. “My dad never knew how to laugh. He would just make a noise, but it wasn’t a laugh and there wasn’t any humor to it. He never learned how to laugh, how to be a child, how to play. He learned none of that.”

On one of Jean’s last trips up north to visit her family, Jean had the opportunity to begin learning Dene from her niece. As I ended the interview Jean sent me on my way with “Kutenti” – Dene for happy trails.

Be the first to comment on "Joe and Jean White trace their father’s journey to understand their family history"