Reviewed by Deena Goodrunning

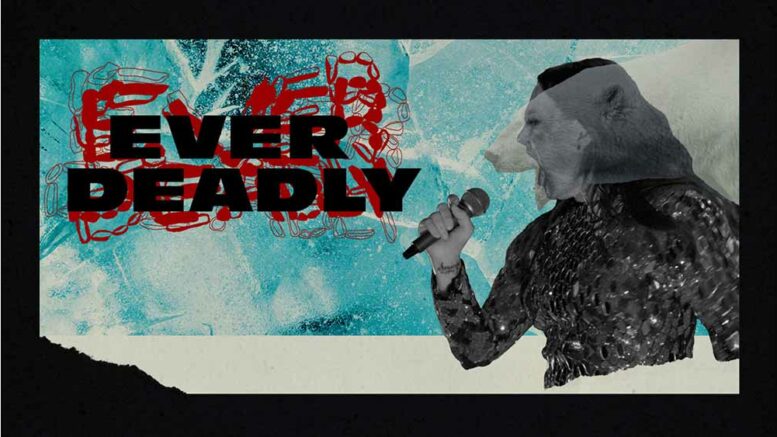

(ANNews) – Ever Deadly is a documentary about award-winning Inuk singer, activist and author Tanya Tagaq. The film was written and directed by Tagaq and filmmaker Chelsea McMullan, and was produced by the National Film Board of Canada. Ever Deadly premiered at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival on September 9, 2022. Since then Ever Deadly has had various screenings across Canada, including two screenings at the Metro Cinema in Edmonton in January 2023, which is when I watched the film.

I was excited for the film since I love listening to Tagaq’s music and her book Split Tooth is one of my favourites. But, despite being a fan I didn’t know too much about her – except that I love her music and her book. While the film doesn’t provide a complete biography of her life, it does provide glimpses into her life with a focus on her music and activism.

The film started off with Tagaq traditionally throat-singing with another Inuk artist Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory. At first, I was wondering: what were they doing? Were they simply singing a song together? Were they acting out a story together? Then at one point I realized they were competing with each other. And later on in the film I felt delighted to be proven right when Tagaq described traditional throat-singing as a friendly competition between two women. Tagaq’s throat-singing that is featured in most of her albums is contemporary throat-singing.

In Ever Deadly scenes shot in Nunavut of Tagaq’s life were skilfully entwined with scenes of her performing at a concert. The film also featured animated illustrations hand-drawn by Inuk artist Shuvinai Ashoona and spoken word lines from Split Tooth. The flow was captivating in that the tone of the scenes from Tagaq’s life were being matched with the tone of her singing scenes. Performance scenes where she would be singing in a calmer way were followed by calmer scenes from her life, while scenes where she was singing in a darker and more anguished way were followed by darker scenes. The film actually reminded me of a score of music where each note was paired with the next notes. All the scenes and sequences in the film flowed together very melodiously.

The film and Tagaq’s music was creepy and scary at times. But, I didn’t mind. In fact, I welcomed the creepiness and scariness of the film and her music. Because the world is a creepy and scary place. If people want to criticize Tagaq for having strange and dark sounding music, they should first criticize the world for being a strange and dark place.

Dark situations and topics were shown in the film. Tagaq’s mother tells the story of how the Canadian government forcibly relocated Tagaq’s family from their resource rich community to a new location that was scarce in resources. Her family nearly starved to death, but they managed to survive. The film also brought attention to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women in Canada and brought attention to residential schools and the abuse and assimilation practices that happened.

“Residential schools have beaten the Inuktitut out of this town in the name of progress and the name of decency,” Tagaq said at one point in the film.

People were using their power to harm others. And most people didn’t care to stop it because it was Indigenous peoples being harmed.

Despite addressing such dark issues, the film was also really funny at times. There was a sense of humour and healing throughout the film. When Tagaq was asked if other animals besides fish also have hearts that continue to beat after they die, Tagaq remarked that she doesn’t know. She thought for a moment and then said that maybe chickens do.

I’m not capturing the sense of humour in that scene through my writing, but watching it in the theatre almost everyone around me was laughing. The audience members around me were also laughing when Tagaq humorously said at one part in the film, “I don’t want people to visit my grave. I hate people!”

In conclusion, I really loved Ever Deadly. The film was so beautiful and stunning and was (just as the title suggests) ever deadly. I would really recommend that everyone watch the film. The messages and truths that the film tells on the historical and ongoing impacts of colonialism in Canada are incredibly important.

And even if Ever Deadly had only shown concert footage scenes, the film would still be incredible just for the pure beauty and radiance and darkness of Tagaq’s music and singing. Plus, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a film shot and cut together in the way this film has been. Something about the way the film was edited and directed really gives off a sense of it being a song almost.

However, I will acknowledge that the film and Tagaq’s music might not be everyone’s cup of tea. Both the film and her music are very different from what most people would normally see and hear. But, as Tagaq said herself in the film: “It’s a very small room, so if you really hate it, it’s easy to leave. It’s just a few steps that way.”

Deena Goodrunning is a Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Be the first to comment on "Ever Deadly: A documentary of power and song!"