by John Copley

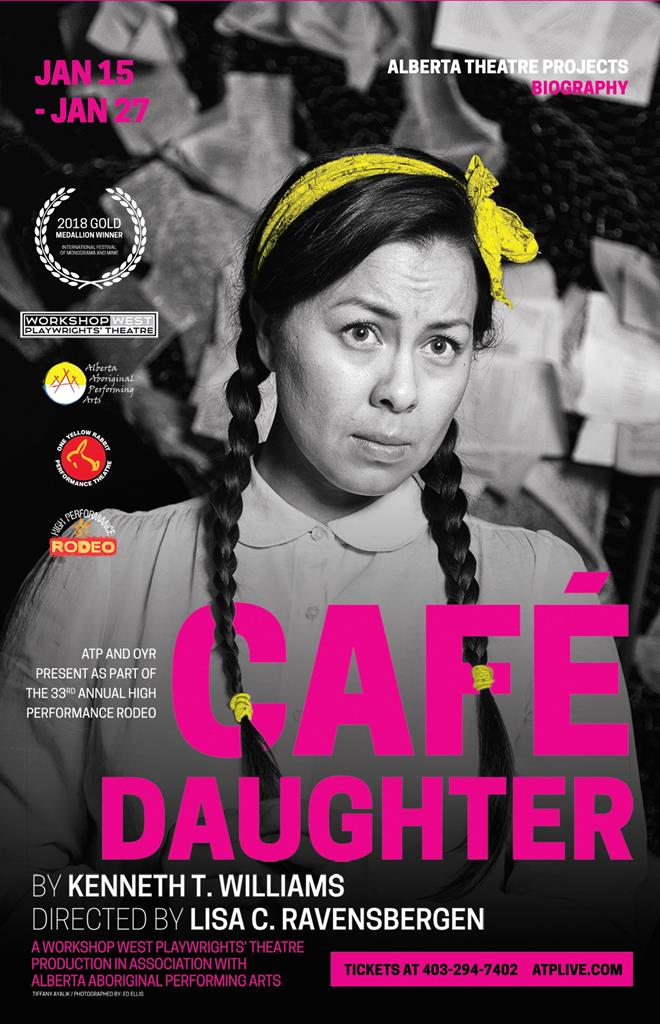

(ANNews) – Theatre-goers in and around the Calgary area are in for a special treat this month and it all takes place from January 15 – 27 at the Alberta Theatre Project’s Martha Cohen Theatre where Workshop West Playwrights’ Theatre (Producer), in association with Alberta Aboriginal Performing Arts will present playwright Kenneth T. Williams’ family-friendly production, Café Daughter. The play, directed by Lisa C. Ravensbergen, takes place in three separate time spans, beginning and ending in the 1970s with the bulk of the action taking place in the 1950s and 60s. The Alberta Theatre Projects production is a part of the 2019 One Yellow Rabbit High Performance Rodeo.

Café Daughter tells the story of Yvette Wong, a nine-year-old girl of Chinese and Indigenous heritage that grew up in a small and somewhat race-intolerant town in Saskatchewan in the 1950s.

“The inspiration for the particular script comes from the life and history of Cree Senator Lillian Eva Quan Dyck,” noted the playwright. “I first met Lillian Dyck in 1999 while working with the National Aboriginal Achievement Foundation. The award gala took place in Saskatchewan that year and I was tasked with finding Saskatchewan recipients for the annual awards. One of my cousins suggested Lillian Dyck.”

She was subsequently nominated and did win a National Aboriginal Achievement award that year.

During their meetings over the next few months Williams learned a great deal about the Cree Senator including her life growing up as a half-Chinese, half-Cree girl. In the end he came up with a fast moving and uplifting story that proves that despite all odds, if you know yourself, believe in yourself and seek your place in the world, you can realize your dreams.

Kenneth T. Williams is a Cree playwright and a member of the Gordon First Nation, a Treaty 4 community located northeast of Regina. From age 12 through his early adulthood he lived off-reserve in Edmonton. He graduated from the University of Alberta with a Bachelor of Arts in 1990 and in 1992 he became the first Indigenous person to earn a Master of Fine Arts Degree in playwriting from the University of Alberta.

During his conversations with Lillian Dyck, also a member of the Gordon First Nation, Williams learned that just 70 years ago, white women were not allowed to work in Chinese restaurants – a result of the province’s Female Employment Act (1912), a law that made it illegal for Chinese restaurants to hire white women.

In the play, a Chinese immigrant, Charlie Wong, comes to Canada, opens a Chinese restaurant and hires a First Nations (Kathryn) woman to work in his restaurant. Over time they fall in love, get married and have a daughter they named Yvette. She is the main character in Café Daughter. A bright and enthusiastic child, Yvette is placed in a slow-learners class because of her heritage. Her mother, who’d earlier been forced into residential school, warned her daughter not to reveal her Indigenous heritage – to keep it a secret. When her mother passes away, she and her father move to Saskatoon where Yvette is put in the position of having to pursue her destiny alone.

“I was really astounded when I first learned that at one time Chinese restaurants weren’t allowed to hire white women,” noted Williams. “I spoke with a friend named Steve Lock; he is Chinese and possesses an extensive resume when it comes to working with Chinese history and immigration. He hadn’t ever heard about it either; we both agreed that we had more than a story to tell, we had a movie – and that’s how the project started. We started working on the project as we pursued it as a film.”

The information they gathered, however, proved to be so immense, he explained, “that it became very difficult to find the focus of the story.” The magnitude of the past has many tales to tell and the information they gathered proved to be overwhelming.

When a Whitehorse theatre company put a call out for proposals, Williams knew what he must do.

“When the search for proposals was advertised, I think it was in 2008, I spoke with Keith and told him that I needed to go back to what I know best – writing plays. He gave me his blessing and I got down to work and wrote the spine of the story, realizing that maybe one day we could look at creating a movie.”

Café Daughter is a one-woman show that runs about 90 minutes without an intermission; the star character, Inuit actor Tiffany Ayalik portrays a total of 13 characters, each uniquely different from one another and each with sometimes very opposite opinions. Other than Yvette, her characters include her Cree grandfather, her Chinese father, a racist bully and a supportive teacher who ends up turning against her.

Café Daughter first appeared in 2011 and made its debut in Edmonton in 2015 when it was produced by Workshop West. It was nominated for a Sterling Award for Outstanding Production in 2016 and was warmly received in every major city the play visited on its nationwide tour across Canada.

Other Williams’ productions include In Care; Street Corner Playwright; The Story of Saskatchewan; Weesageechak Loses his Bum; The Righteous Woman; Gordon Winter; Bannock Republic; Suicide Notes; Three Little Birds and Thunderstick. Eight of his plays have been produced and six have been published.

Currently an Indigenous Theatre teacher in the University of Alberta’s Drama Department, Williams said this story is another that will give Canadians a better education and insight into some of the things that transpired in the country’s past.

“I know when I talk about these things in a classroom the students are surprised to hear about some of what took place in our past. They can’t believe some of this stuff happened and I tell them that I continue to learn more about Canada’s history every day.”

Williams has been teaching at the University for two years and said he’s happy to be back in Edmonton and “really enjoys the city, the university and the students the teaches.”

The author/playwright said the inspiration to write plays comes primarily from is overactive imagination and his desire to do something with it.

“I had thoughts of becoming a lawyer at one time,” he chuckled, “but nothing developed; I think I became a writer because I had little other choice at the time. Initially I wanted to write novels and I tried it for a while, but I wasn’t really good at it. Drama came purely by accident; I began attending university in 1983 and was trying to get into the creative writing program that they have here but I didn’t have enough of a portfolio to be considered. A friend of mine told me that there was a play writing class being offered by the drama department. I got in and the rest is history.”

What do you want audiences to take home from this play?

“I try to write as pure a story as I can so that you don’t think about the unspoken, including the facts that caused the play to happen in the first place. Nowhere will you see mention of the Chinese Immigration Act or for that matter even the Indian Act – you are however, going to see what life is like because of that legislation.

“What I like about theatre as an entertainment and art form is that it is so intimate – you cannot really escape the feelings you’re going to have because you’re seeing the people live and right in front of you. It has an impact that I believe is far greater than you’ll find in a movie or film because you can switch them off, but a play brings a sense of reality and it’s right in front of you. I hope people are just generally moved by the story; they might not be radically changed because of it, but they will go away with more knowledge about Canada’s history.”

The inspirer of the play, Lillian Dyck, was born in North Battleford, Saskatchewan to a Chinese father, Yok Lee Quan, and Cree mother, Eva Muriel Mcnab. Her father came to Canada after paying the Head Tax, leaving his first family behind in China. Her mother was born on the Gordon Reserve, but lost her status when she married a non-Indian. She, like most First Nations women at the time, was sent to a residential school.

Dyck moved around a lot, living in many small towns in Saskatchewan and Alberta, her family hiding their Indigenous heritage in order to protect themselves from racism. Taking her father’s last name of Quan, her family was essentially the only Chinese family in town. As most First Nations people were living on reserves, she had no connection to them. Her family was the only non-white family in town.

She attended the Swift Current Collegiate Institute and later (1968) earned her Bachelor of Arts Degree (Honours) and in 1970 her Master of Science Degrees in Biochemistry, as well as her Ph.D. in Biological Psychiatry in 1981, all from the University of Saskatchewan. She was conferred a Doctor of Letters, Honoris Causa by Cape Breton University in 2007. Before being appointed to the Senate, Dyck was a neuroscientist with the University of Saskatchewan, where she was also associate dean. On March 12, 1999, Dyck, one of the first Aboriginal women in Canada to pursue an academic career in the sciences, was presented with a lifetime achievement award by Indspire. Her research focuses on mechanisms of action of monoamine oxidase inhibitors to identify drugs useful for treatment of neurological disorders and stroke. She continues to teach at the university as well as conduct research on a part-time basis. She was appointed to the Senate on the recommendation of Prime Minister Paul Martin on March 24, 2005.

To learn more about Café Daughter and to book your tickets visit the website at atplive.com.

Be the first to comment on "Café Daughter brings inspirational story to Calgary audiences – at ATP until January 27"