By Dale Ladouceur, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

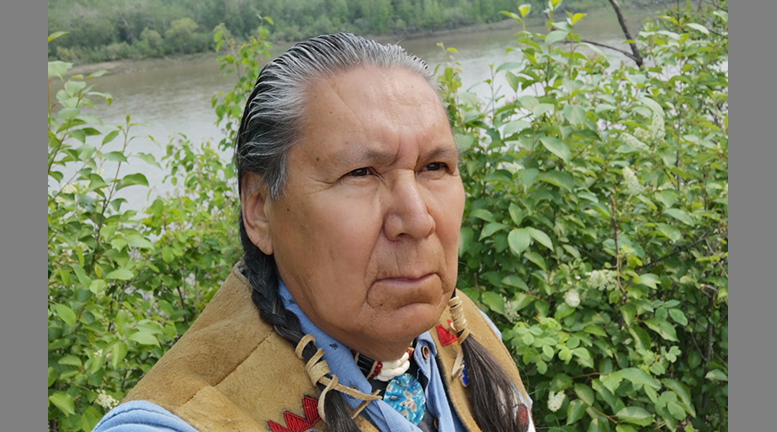

(ANNews) – I first met Elder Snow a few years ago, jumping at the chance to go Sweetgrass picking for the first time with Bent Arrow Traditional Healing Society. He is a quietly charismatic man who exudes a calm and steady presence. I approached the soft-spoken Elder for guidance and we soon became friends, honouring my family with my daughter’s naming ceremony.

What I find draws most people to Elder Snow is his generosity in sharing his teachings that were born from a life story of resilience. I recently spoke with Elder Snow, eager to hear his calming voice and wise counsel amid tumultuous times.

“I believe a lot of people may strive to be something they want but because of a lack of natural experience, it is challenging for them to be in that place they want,” he remarked. So much of what I wanted to discuss with him was addressed with this response.

Prompting him to share from his history and what he draws strength from, Elder Snow took a long, slow breath and began. “The earliest thing I remember is horses. All the time: sleigh-riding, pulling our wagon or me riding a horse. Most of the time we were camped out in a teepee or tent and when we went home, we lived in a log cabin with no running water. We gathered wood for the stove and for heating, so I was always in touch with nature. I lived this way until I was old enough to go to Residential School. I was there for a year and then my father took me out and put me in the Day School when I was seven.”

Snow, like many Residential School survivors, blocked out much of that experience. He spoke of trauma, abuse and humiliation but luckily his parents intervened. “Because my parents noticed I was not myself, they put me in Day School, and shortly thereafter I began to have anxiety attacks at night.

“At night there’s nothing open, no health centres. So my father would put me on the back of the horse, we would ride double and he would take me to a medicine woman. She was very old, I remember the medicine woman smudging me and praying and talking to my father about traditional things and what was happening to me. Some of [the talk] I didn’t understand because it was a higher form of Nakoda language. I would feel better after this as I was riding home. I don’t remember much else except getting off the horse, walking in and sleeping soundly.”

After grade six, Tom’s father pulled him out of Residential Day School and put him in a public school in Exshaw. “When I left the Residential and Day Schools, I was a real mess: thin, frail, sickly. It was the abuse of what happened there: I couldn’t speak my language, teachers were yelling, throwing stuff at us.”

In Exshaw, the culture shock was reflected in interactive behaviour. “In the Residential Schools it was a bullying atmosphere and, [because of this], my typical reactions were not appropriate for public school. If somebody teased you in the Residential School,” Snow explained, “you would defend yourself. You can’t do that in public school, but that’s what I had learned.”

The other piece of culture shock was in education. “I remember the first time the art teacher came in and said, ‘Ok class we are going to be doing converging lines, so I want all of you to draw a bowling lane.’ I had no idea what a bowling lane looked like! So, I had to look at the other students’ work to see what was going on and mimicked them.”

Tom was a pretty good student but the difference in culture had a negative impact on him, affecting him deeply. By the time he was in grade ten, his self-esteem and self-identity had been “really quashed.”

The death of his father during the first month of grade 11 caused a downward spiral. “I couldn’t face the class or be productive so I dropped out. That started me on my drinking path.” One bright spot during this dark time was “a godsend of a program called the Stony Wilderness Centre.”

The program was 12 days: three days Indigenous culture orientation, three days of horseback riding into the mountains and a three day camping backpack trip. Unfortunately the program stopped and Tom’s drinking went from bad to worse, staying that way for ten years. “Alcohol really humbles you.” He confessed, “I ended up in downtown Calgary, at times homeless, in the gutter.” Snow went back to the reserve “…with completely nothing except my mother.”

Luckily Snow’s desire to learn and grow caused him to sober up and self-reflect with a reoccurring question: Why am I like this? He started to research indigenous perspective histories, initially calling his own research The Effect of Histories. “It was an investigation into what had affected me to be face down in the gutter with all of my potential.”

His deep-dive research into Intergenerational Trauma, Residential Schools and the Indian Act, taught him that “the way I was; it was not all my fault. I thought I was not good enough, my parents were too poor to help me. I was blaming myself, my parents, my grandparents. The research was a revelation of what had occurred.”

Snow explained that “from 1884 to 1951 practicing traditional beliefs and practices were banned and many had to go underground.” If Tom Snow was going to walk a true, traditional path, he was going to draw from the true Nakoda practices he had experienced as a child.

“I went searching, all across Nakoda land from Alexis/Nakoda all the way down to Pine Ridge (South Dakota)/Lakoda land, west to Manitoba. I was looking for affirmation about my traditional Nakoda beliefs.” He found it in Pine Ridge SD. “When I went to Ft. Peck Montana and attended ceremonies, I also found traditional Nakoda teachings.” It rang true and energized him, removing the fear he had felt. “It affirmed my belief and gave me a foundation.”

During this time, he was mentored into ceremonies. Snow found that within the sweat lodge songs were gems. “Because I’m fluent in my language, I found a lot of traditions that were actually hidden within the songs. As time went on, other medicines started coming to me: visions and songs, dreams and people. “Remember the white buffalo in ’92?” asked Snow. “That was foretold by one of my mentors two weeks before it happened. And I was actually sent there, to Janesville, Connecticut.”

Snow explained that it was not one thing that enabled him to heal. “It was the actual plants, songs, dreams, talking around campfires, sitting around a sacred sweat fire, dancing at a Sundance – all of that is part of healing yourself.”

And now, walking a healthy path and with healthy relationships, Elder Tom Snow spends his days “… along the mountain, (Calgary, Canmore, Cochrane, Banff), helping to heal others,” by practicing pure traditions.

Hello i am looking for a medicine man to do a cleansing in a troubled young man in the Edmonton area