By Laura Mushumanski, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

(ANNews) – There is a glacier-fed river thriving with phytoplankton while sharing nutrients with all our relatives and flowing freely through the center of amiskwaciwaskahikan, Beaver Hills House, Edmonton, Alberta. It is a sacred gathering place named after the Beaver Hills people, our ancestors and caretakers of the land. You cannot come to know and understand this river through written word nor technology of any kind. Understanding comes only when immersing yourself with the original teachers of reciprocal relationships within our natural environment and by visiting these relatives – often.

As you continue to visit the land, this new knowledge that the spirit of the land is teaching you will start to teach you about life through different ways of knowledge and knowing. You will be supported in coming to know things differently than what previously held assumptions about life, love, and living have taught you.

For as long as it has been here, the river itself, our living relative – this mighty force of strength – has brought nations together. It has fed, nourished, transported, protected, and connected us to each other.

The North Saskatchewan River, that “teaches us to think with story,” continues to flow just like the blood that runs through our veins. This is our salvation and one of our greatest teachers. No words can describe the essence and spirit of our living relative, this body of water, as it would never be able to equate to the sacred ecology and wisdom embedded in the emotional, mental, physical, and spiritual insight it continues to gift us as it does life.

These experiences become part of us as we think with story, walking alongside how these teachers teach us to connect intimately and deeply with any body of water, just like with any part of Mother Earth. This is the innate understanding that holds the capacity to teach our ecological relationship through humility. It is the most sacred relationship we two-legged humans have the honour of building, strengthening, and caretaking while we are living and breathing inside our physical bodies. Because the natural environment exists, so does everything else that resides on Mother Earth and it is up to us to be good relatives in return.

The more time spent visiting and learning about our relatives, the ones that care deeply for us without ever asking for anything in return, the more curiosity will grow of wanting to know more about these sacred relationships. In turn, one of these sacred teachings that comes from the land is embedded in the spirit of humility.

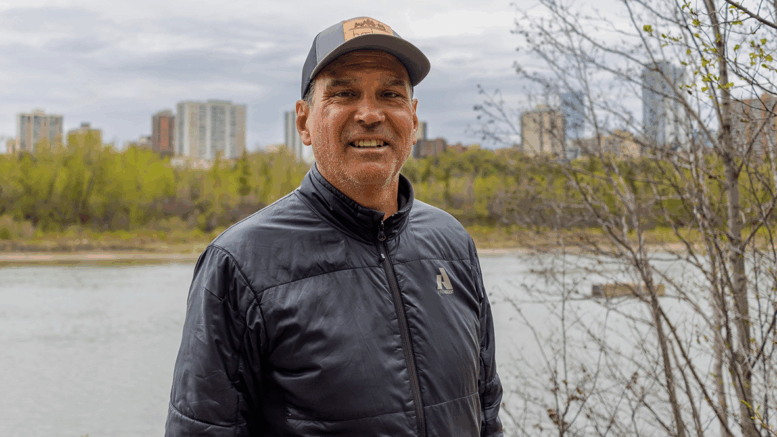

That same initial curiosity was shared with me while visiting with our brother, Dwayne Donald, and how story began to unravel in front of him – exploring how stories and places started to shift and shape his perspective on the world around him and what it means to be in relationship with the land. Teaching him how to “walk [him]self into kinship” – wâhkôhtowin.

At first, it did not cross Donald’s mind when thinking about ecological relationships, how “if the beautiful river is unhealthy and polluted, so are human relations” – and what that means.

Being connected to amiskwaciwaskahikan all his life, it wasn’t till Dwayne started his teaching career with the Blood Tribe that gifted him insight into stories and places that led him to learning about his shared kin relations with the Beaver Hills people and the Papaschese Cree. “I didn’t know anyone down there, I just needed a job,” he explained. “So here I was, this kid from [Edmonton]…and I went down there [to Kainai] … Where things changed really drastically for me was when I got a job teaching at Kainai Highschool.”

Donald continued, “This wasn’t something I planned…. That experience [with Kainai] changed my life… It really caused me to reflect on a lot of things I didn’t have much experience with before. Things I was really curious about … stories and places – how my Blackfoot friends exposed me to how they map their territory according to stories and ceremonies.”

Donald spent 10 years teaching in Kainai. This is where he learned how to pray – a different way of connecting and understanding outside of what he was familiar with.

“We didn’t [pray] when I was younger. We rarely went to church … it just really wasn’t part of our life… [This is] where I realized the difference between the church and spirit.”

Realizing that “there were a lot of things I didn’t understand very well,” supported his decision to go back to school to obtain a Master of Education through the University of Lethbridge, focusing on Aboriginal Education. Then in 2009 he convocated with a PhD in Secondary Education from the University of Alberta; his dissertation was ‘The pedagogy of the fort: Curriculum, Aboriginal-Canadian relations, and Indigenous Métissage.’

“There were a lot of influential people in my life, including my partner Georgina, who just encouraged me…just said ‘you should keep going with that’… Multiples times I had people who I really respected a lot, that passed away now, told me that I had a very specific role, to try and help people understand each other better, to improve relationships, specifically between Indigenous people and Canadians … to try and bring people together.”

Another big factor in Donald’s life is his relationship with kehtaya Bob Cardinal. Reflecting on the past 15 years, Dwayne shared, “I feel really privileged that [kehtaya] has come to trust me as an oskâpêw – that also has been a major influence in my life and my work… It’s almost like my role as a professor is parallel to my role as an oskâpêw (helper), and how they kind of inform each other. Being a helper in that way has really brought a lot of really good things to my life, my family, and just given me a chance to learn in all kinds of different ways. And again something I never really imagined myself doing, I am just really grateful”.

Donald, a professor within the Faculty of Education, Secondary Education Department at the University of Alberta, holds a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair position in Reimagining Teacher Education with Indigenous Wisdom Traditions. His work within academia focuses on enhancing and expanding curriculum and pedagogy through Indigenous Wisdom Traditions.

“All those things kind of flow together [and] have kind of created… this standpoint from which I can see things [and] understand the work… I can understand my role, I can understand what is missing from a lot of people’s educational experiences these days,” Donald explains, relating it to his current research with curriculum and pedagogy – the method and practice of teaching.

“One of the things I have learned to pay attention to is how I have been institutionalized through all the time I have spent in school, in university – and how my own kind of understanding of myself and how I think has been so affected by that… When I think about relationship, you can of course be trained to think about it in a purely human kind of way. I think this is the misunderstanding I had early on in my career – say Indigenous-Canadian relations, I only really thought about it in a human-centric way … that recenters all the knowledge traditions that were brought over from Europe, represent[ing knowledge] as kind of the [only] answers to the questions you might have.”

As a learner himself, Donald continued to be curious and engage with what his understanding of relationships were. As he reflected on this part of his journey, Dwayne spoke to “what I have learned about relationships is its multi-dimensional character, quality – it’s fluidity as well – how it moves and morphs… These days I tend to think more about ecological relationships. I think it is about balance, relationships…It’s about reciprocity, about understanding responsibilities and obligations.”

Understanding the responsibilities and obligations to our relationships with our living relatives within our natural environment and taking care of them is deeply rooted in wâhkôhtowin. We take care of each other is how Donald has come to understand kinship.

“What I have been telling people lately is if we want human relationships to be more ethical, then we need to pay attention to our ecological relationships, because those two things are directly connected. If this beautiful river we live beside is unhealthy and polluted, then human relationships will be unhealthy and polluted. This sort of multi-dimensional dynamic is really interesting.”

Indigenous Wisdom Traditions, also known as Indigenous Ecological Knowledge, are rooted in the understanding that all life is sacred – all our relations, including the waters that gift every living organism life and as humans to honour these sacred relationships and take care of them as if they are our own kin. This understanding is rooted in how Donald engages with being a helper, whether in higher education or as an oskâpêw, sharing with us, “to take seriously the ecological and its effects on us as human beings and understanding that balance in terms of how we recognize those ecological relationships. How I understand my relationship to water and what is does to me as a human being. And then how that in turn would play out in how I am with other people. What this has to do with Indigenous-Canadian relations is if we want a better relationship with Canadians then we have to start with the ecological, our shared interest in the ecological. It is only from there that a different kind of quality of relationship is going to start to flow. This is very much a Treaty teaching as I understand it.”

The understanding of Treaty relations has been misunderstood, according to Donald. “We already have treaties with all the life around here, and if you are going to live here with us, then you need to understand those treaties but that part of the discussion was never translated very well or taken seriously… I think we have a chance to try and revisit some of that and lift it. That is how I tend to think about relationships…I think that anything I have to offer in terms of relationality comes from being outside and paying attention to my ecological relationships and of course learning about them under the mentorship of Bob and others – not just talking about them, but living that way, having the chance to be immersed in that way of being.”

Over the past 20 years, as an outdoor runner, Donald continuously immersed himself into life that surrounded him alongside the North Saskatchewan River. This is how he came to know and understand teachings shared with him. Where he began to walk himself into kinship, bringing his existing life to a rich transformative learning experience – reorganizing neural pathways within the body, neurophysiology and understood as healing, and how over time knowledge being walked with and embodied becomes wisdom.

“It was the ecological relationships that were supporting me and guiding me. I think about it now, I was just drawn to the river, I just wanted to be beside it, and walking [and running outside] was my medicine and still is. All this life in this area just taught me about myself, how to fix myself, and I continue to rely on it.”

These lived experiences that have morphed and transformed Donald’s own relationship with the ecological brought him to the understanding of pedagogy through Indigenous Wisdom Traditions as ‘unlearning,’ rooted in teaching and learning. “It is kind of like an unraveling of previously held assumptions. It’s a series of engagements that you have that caused you to realize that you misunderstood…or things that you accepted as common sense, or just the way things are that you started to question … Unlearning – I would say it has three aspects to it.”

Donald’s own understanding of place and connection to the North Saskatchewan River created stories for him of how his relationship with knowledge and knowing with the ecological unraveled his previous held assumptions of life, love, and learning through Indigenous Wisdom Traditions and teachings from the land.

“[The first aspect] is sort of a past, present, future study of the ways in which relationship denial has influenced you and your education. In a certain sense, the task is to work backwards from the present to try and trace out, like genealogically, how things came to be how they are… But it is also about the future, because it is also about trying to proceed differently. It is a mix of past, present, future, an interrogation of [our shared] inheritance of colonial worldview.”

The original teachers of reciprocal relationships are our living relatives that gift us life. When Donald began his journey embodying the practice with prayer, teaching him about spirit, his Blackfoot friends were teaching him about stories and places as multi-dimensional ways of engaging with knowledge and knowing – different ways of being and engaging with knowledge and knowing.

“The other thing is that through our education, we have a particular relationship with knowledge and knowing, that comes from European knowledge traditions. Everything that happens in schools locates us in the same place in terms of knowledge and knowing, even if it is an Indigenous course – it still relies on the same assumptions of knowledge and knowing. For unlearning to take place you need a different experience with knowledge and knowing so that you move out of that dominance of a European understanding – so you are always located at the same point, and you need something that locates you differently. People need to locate themselves differently in relation to knowledge and knowing.”

The ecological relationships that Donald spoke about, that he engaged with over time and built a connection with by visiting our relatives in nature, shape shifted and morphed his own relationship with knowledge and knowing – as a form of healing within the body – through teachings that the spirit of the land was innately teaching him about life.

“The third aspect is what we are calling the paradigmatic provocation. That is a fancy way of saying, that if I want you to understand differently, I have to teach you differently…Like, I could have the most awesome PowerPoint on Indigenous Knowledge, with all the most interesting information – but, if it is presented in a way that people are used to, it’s not going to matter that much. So, we have to follow different approaches to teaching and learning so that people have a different relationship with that knowledge or that knowing.”

Over the years, Donald started bringing people together, teaching about what he has come to know differently and his relationship with our natural environment through walks he hosts alongside the North Saskatchewan River in amiskwaciwaskahikan. This is one of the ways he engages with learners and approaches teaching so that relationships with knowledge and knowing, these seeds being planted, start to unravel misunderstood teachings of life, love, and living through Indigenous Wisdom Traditions.

“These three factors together are what instigates this unraveling… I think the really difficult thing about unlearning is that it really has to do with how you live your life and what you give yourself to. It’s not just a one event thing that can be accomplished in a day. It has to be constantly revisited and resupported… a sustained engagement… Without those three, we found that things really don’t change for people, their relationship to knowledge and knowing isn’t transformed, it’s just more information… This is the biggest problem we face. Universities are ramped up in digital approaches, webinars, being online, so it continues to have a problematic relationship with knowledge and knowing that just reinforces the problems we already have.”

Be the first to comment on "Understanding ecological relationships, knowledge and knowing with Dwayne Donald"