A solid identity is crucial to the essence of any human being. It distinguishes you as an individual and as a member of a group or community. The loss of identity through adoption can sometimes have devastating effects, and even more so if the child is placed with a family outside of their own culture.

In Canada, statistics from Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development show that over 11,000 Status Indian children were adopted between 1960 and 1990. However, it is speculated that the real numbers are significantly higher. During this time period 70 per cent of the adoptees were placed into non-Aboriginal homes. As a result of being disconnected from their heritage the report also found that a large portion of these individuals now struggle with cultural and identity confusion.

Although the disproportion between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal in the child welfare system is still greatly visible, there are generations that are now reconnecting to their culture in a powerful way.

Amanda Gould, a soft spoken, dark haired woman with pretty, almond eyes that are warm and welcoming, yet fierce and bold, is hard to mistake for anything but having Aboriginal DNA. Maybe it’s her long tresses that she decorates with intricate beaded jewellery or the subtle whiff of sage around her – an ever constant perfume of prayers, that’s a dead giveaway. One thing is for sure, she is not hiding her ethnicity, but displaying it proudly with the eagerness of a blossoming flower.

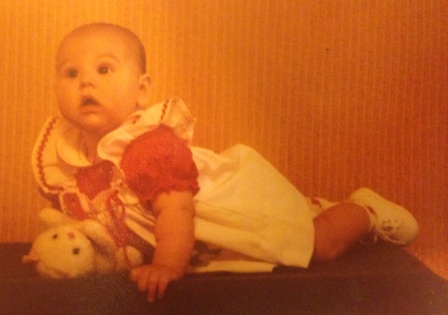

Baby Amanda was adopted into a non-Native home and she struggled with her identity throughout her formative years. Article by Brandi Morin

There was a time when Gould walked a desolate road of confusion that eventually lead her on a journey to self-discovery and cultural awakening.

Adopted into a Caucasian family at birth in 1978, Gould said from a young age she was treated differently but didn’t understand why. She had a good upbringing, yet she had an awareness that she was Aboriginal because it was pointed out.

“I was the one in the family always known as the Indian kid,” she said. “But I didn’t see color. I thought I was the same as everyone else.”

One day in Grade 3 she was abruptly pulled out of class along with other dark skinned, Native children to attend a smudge ceremony. Not much was explained, so afterwards she didn’t think much about it, except to notice that she was set apart from the other kids in the predominately white school.

Later on her parents brought her to a few powwows to set up tables and sell merchandise where Gould believes having a Native child with them helped in soliciting sales.

In the distance, she would hear the singing and the drums would strike to the beat of her searching heart, but they would soon fade into the blurred divide between the two worlds.

In an attempt to bestow some sort of cultural sense to their adopted daughter her parents bought her literature on Indians, but mostly of the romanticized type. From there more than ever, her fantasy of finding her birth family was starting to grow.

During this time she was exposed to the stereotypical view of what it meant to be an Indian. Living on 118 avenue in Edmonton, a rougher part of town, known at that time for its rampant presence of crime, drugs and prostitutes, she saw many Aboriginal people engaged in these activities.

Amanda Gould has overcome many obstacles and she is now on a journey of self discovery that includes cultural awareness and powwow dancing.

This experience led her to believe that being Aboriginal meant being an alcoholic and a drug addict. Meanwhile, she was still treated negatively because of the color of her skin. She grew up being talked down to and constantly told she wasn’t smart enough to accomplish high aspirations.

After Grade 9 she quit school and at age 19 she became pregnant and gave birth to a son. At the time, her circumstances to raise a child were not ideal so she gave him up for adoption.

Two years later while pregnant with her daughter, who is now 14, Gould mustered up the courage to take the steps to track down her birth family. Putting an ad in the Edmonton Journal proved successful when her mother’s sister got in touch to connect Gould to her family.

“I found out my birth name is Baby Girl Cree and I’m from Fort McMurray First Nation,” declared Gould, with honour and certainty.

She travelled to the land of her people in Fort McMurray on an “emotional” and “intense” venture where she met her birth mother and other family members. It was a good experience, although short, and after witnessing life on the rez, a seed had been planted to discover some of the mystery of what it means to be Indigenous.

For a little while this journey was interrupted by a turbulent relationship which prompted Gould to go into hiding and then give her baby daughter to family for protection. After running from an abusive partner and having nowhere else to turn she found herself feeling hopeless, living on the streets. She tragically fell into a drug and alcohol addiction.

She wandered aimlessly for a few years, grappling with a sense of purpose and questioning her existence and ability to contribute to the world.

“I was empty. I had nothing. I didn’t think I had any purpose to live. I was just a body walking around.”

Then one day she had a humbling encounter that would hereafter change the course of her life.

Amanda Gould got the help she needed to turn her life around. She now enjoys working with Aboriiginal youth and provides guidance and a positive example. Photo by Sean Arceta

“I had an awakening- Creator spoke to me. It was kind of like a live or die situation. (Creator said) ‘You’re either going to die if you keep going this way, or you can change it around and live.’ I didn’t know what I was living for, but I chose to live.”

Terrified about the unknown she checked herself into Poundmakers Lodge Treatment Centre where she said she found her spiritual, Native self.

Hungry to discover her culture Gould flourished while being introduced to the Native world. After successfully completing treatment she got her daughter back and re-started on the path to connect to her roots.

Over the next few years she immersed herself in classes through Alberta Native Counselling Services and attended numerous round dances and powwows.

She got a degree from the University of Alberta Native Studies Program and worked on residential school claims in an Edmonton Law Firm. Much of her free time was spent in proximity with native culture and she even began to attend powwow practice.

The more she drew closer to her heritage and discovered the magic of who she was, the stronger she became and the wounds and uncertainty of her past began to quickly heal.

Last year she was hired as a First Nation, Metis and Inuit liaison and she is enjoying making a difference in the lives of young people.

“I want to be that good example that follows the ways and can be there when children are searching for it or don’t know who they are or understand what being Native’s about.”

Also last year, the spirit of the drum began to beckon and she wanted to follow where it would take her. A dream of one day dancing had been rising within her and she was avid to pursue it. Although deep down she had always wanted to dance, she felt shy and intimidated, so she offered tobacco to a friend and asked her to mentor her.

She began to make her regalia over the course of many months right up until the wee hours before the 2014 Sturgeon Lake powwow. Then she was ready to dance. After all the time, after all the adversity and perseverance she was about to take a powerful step into living out a piece of her identity and becoming the self that she was created to be.

The dance was a symbolic one to honour her friend Bella Laboucan-McLean who had died a year earlier after falling 31 stories off a condo patio in Toronto. It was an extremely spiritual moment that Gould described as “overwhelming,” and “beautiful.”

This summer she gracefully danced in many powwows and now says she wants to keep the traditions of her people alive. And in honour of the Elders who suffered much pain and horrors through the residential school system she is motivated to live the best way she can.

Now, being Native to her has a deep meaning that is hard to verbalize because it encompasses an understanding on so many levels including physical, spiritual and emotional.

“It is one of the most beautiful things on this earth. It’s happiness.”

To anyone who is curious to discover their roots but feeling uncertain or intimidated, Gould urges them to reach out.

“If the people want to dance, they should dance. Just follow their spirit and dance, it’s one of the most amazing things. If you’re scared, approach someone and ask them for help because it makes it a lot easier.”

She keeps in regular contact with her biological family and has a close relationship with her two sisters. She reconciled with her now 16 year old son she had given up for adoption and is encouraging her daughter to take up dancing with her.

Gould is also a passionate advocate for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and she regularly volunteers with Sisters in Spirit.

For anyone in Alberta looking for resources or help to re-connect with their Native heritage, a good place to start is with Native Counselling Services of Alberta. You can find them at www.ncsa.ca

by Brandi Morin

So proud of your accomplishments Amanda. Thank you for sharing your journey and allowing me in your’s and your daughters lives. Love. Laugh and continue to Dream Big.

Love Jenny